Roze Stiebra is considered the "godmother" of Latvian animation. Across six decades of work, she not only established animation as a serious art form in Latvia but also infused it with a distinctive poetic voice. Her films, nearly seventy in total, adapted folklore, poetry, and national fables, always with an emphasis on warmth, empathy, and imagination.

Stiebra’s career spans the late Soviet and post-Soviet eras, and the political climate of both periods is reflected in her work. Stiebra recalled that she and husband Ansis Bērziņš (creator of the Fantadroms series) “deliberately distanced [themselves] and studied only technique, to avoid ideological influence… Making cartoons became a form of protest". In this article, we'll be covering three of Roze Stiebra's films available to watch on Eternal, looking into some of the nuances and references that defined her animation style.

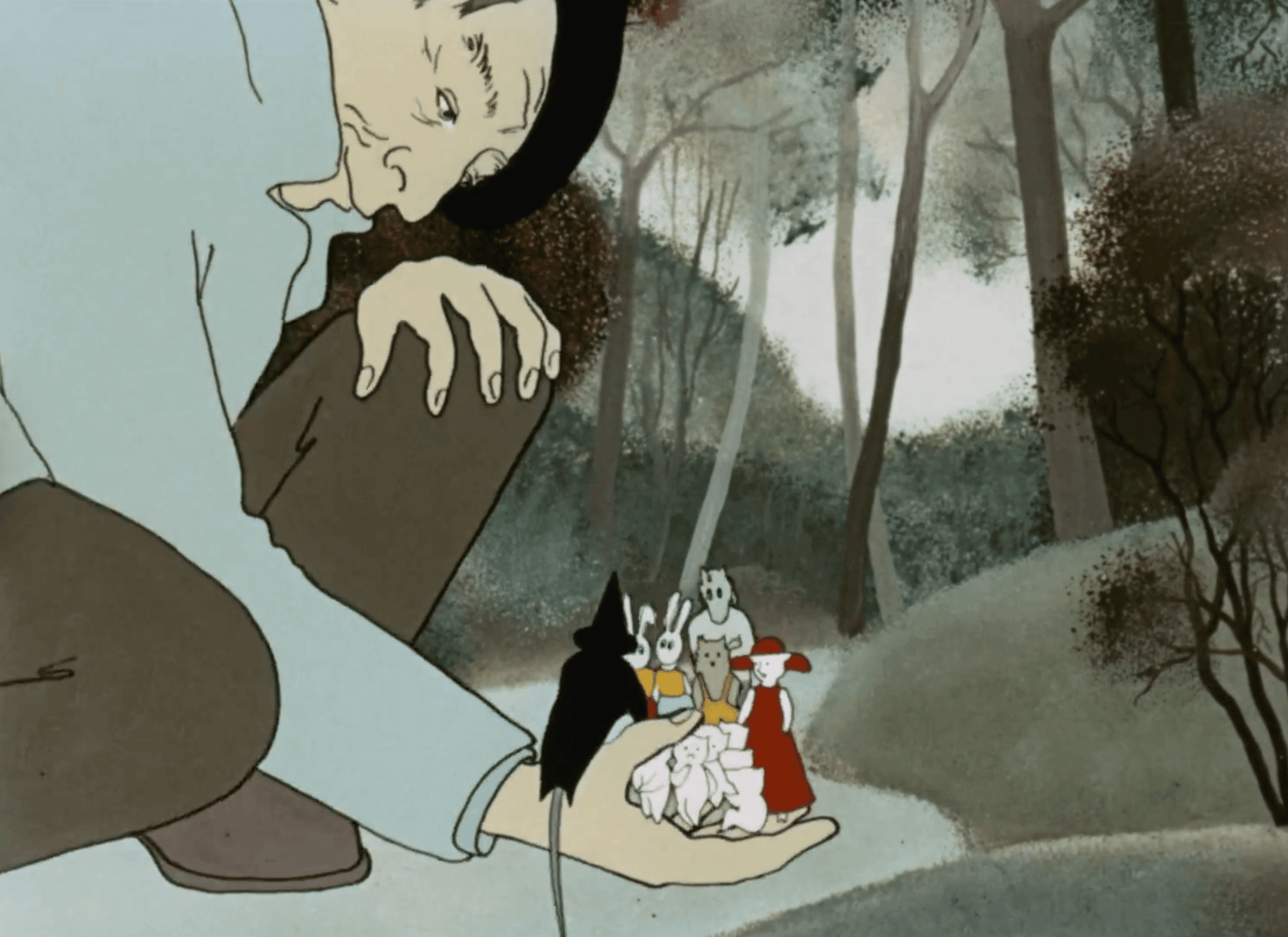

1. In My Pocket (1983)

Roze Stiebra’s first drawn animation after nearly twenty years of cutout work, marking a new phase in her career. Based on children’s poems by Ojārs Vācietis and set to a choral score by Imants Kalniņš. He stands on the bridge, and the little characters spring up from his pocket. They tumble out, and so begins a series of whimsical vignettes: an elegantly dressed mother pig whose babies are stolen by the circus, a green fly afraid of soap, and a romantic wolf gazing at the moon.

The stories themselves are both charming and (in the way children's stories uniquely are) rather intimidating, scaring kids into things like washing their hands and not trusting strangers. Beyond this, they carried into the future fragments of the Latvian culture and national identity which the USSR actively repressed. Throughout the late 80's the 80's the Soviet Union continued to decline, and the idea of freedom for the buffer states started to feel closer and closer. By using Latvian voices, images, and landmarks that would likely only be recognized by Latvian viewers, Stiebra was working subtly to fuel national strength for viewers young and old.

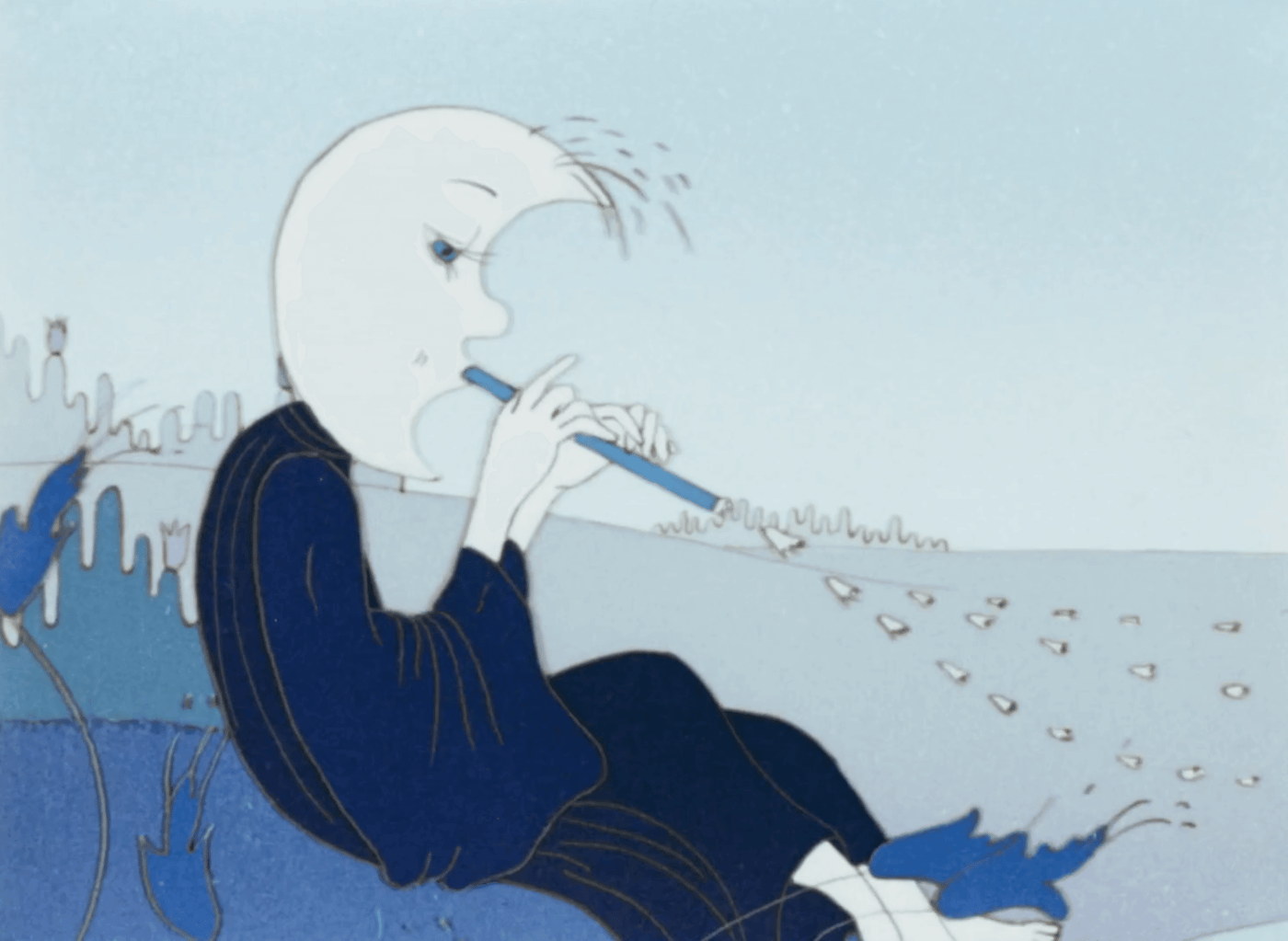

2. A Fairytale Sits on the Doorstep (1987)

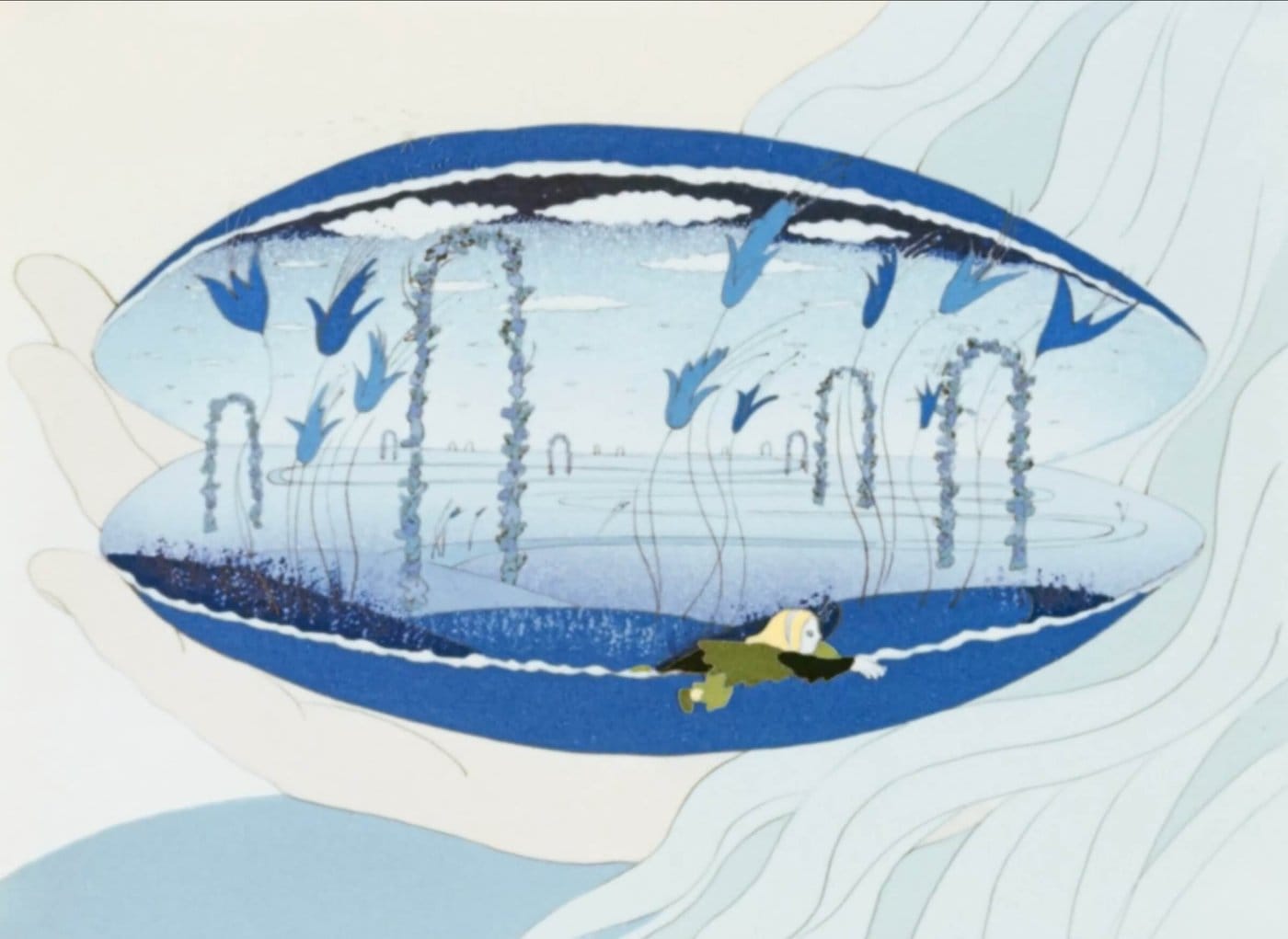

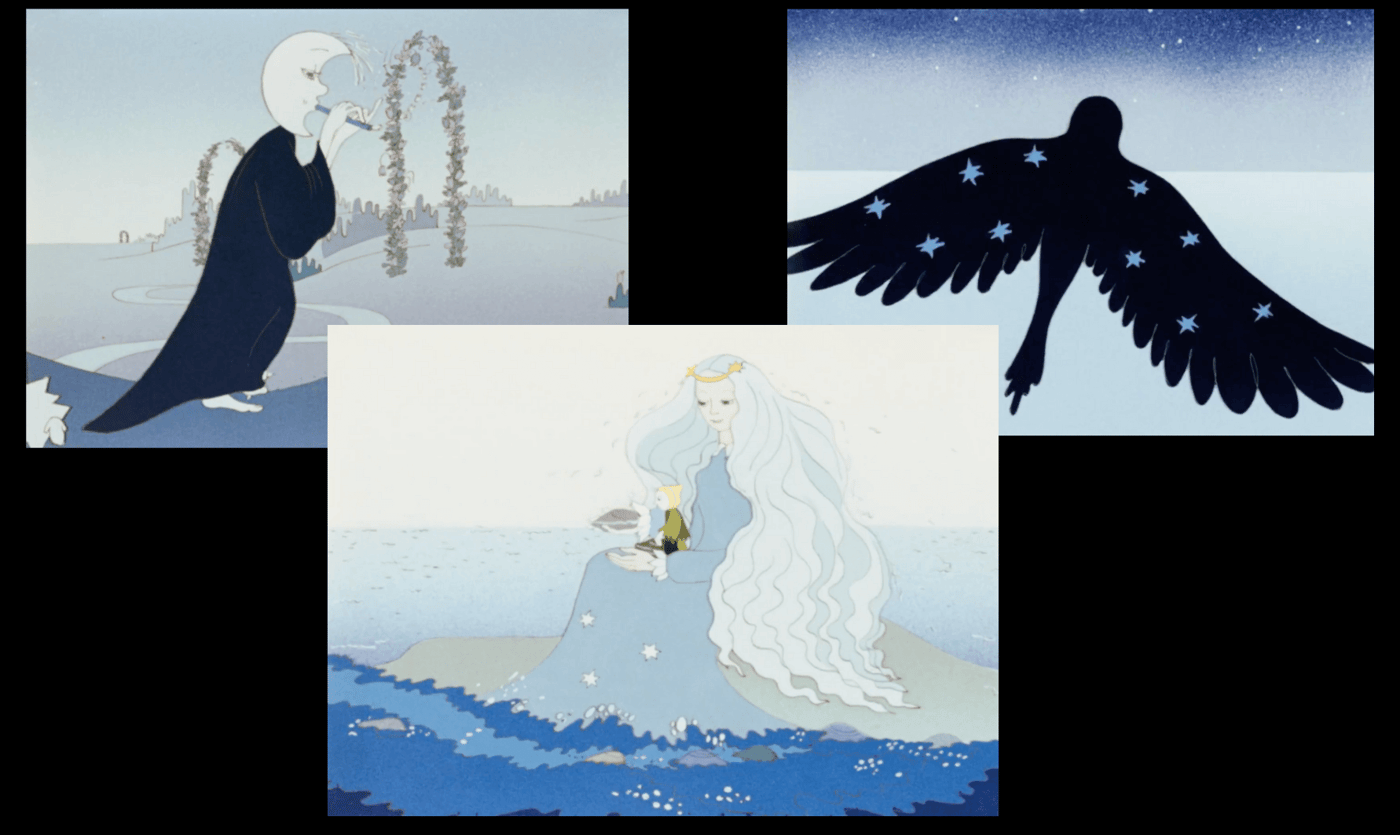

In A Fairytale Sits on the Doorstep, Stiebra brings to life the poetry of Latvian poet Aspazija. Fairytale is the most artistically distinct of the collection, using a palette of deep indigo and pastel yellow and the surreal frame of the clamshell to create a bedtime story feel. The score turns the poem into a lullaby, pairing soft vocals by singer Mirdza Zīvere with the wistful synth by composer Zigmārs Liepiņš.

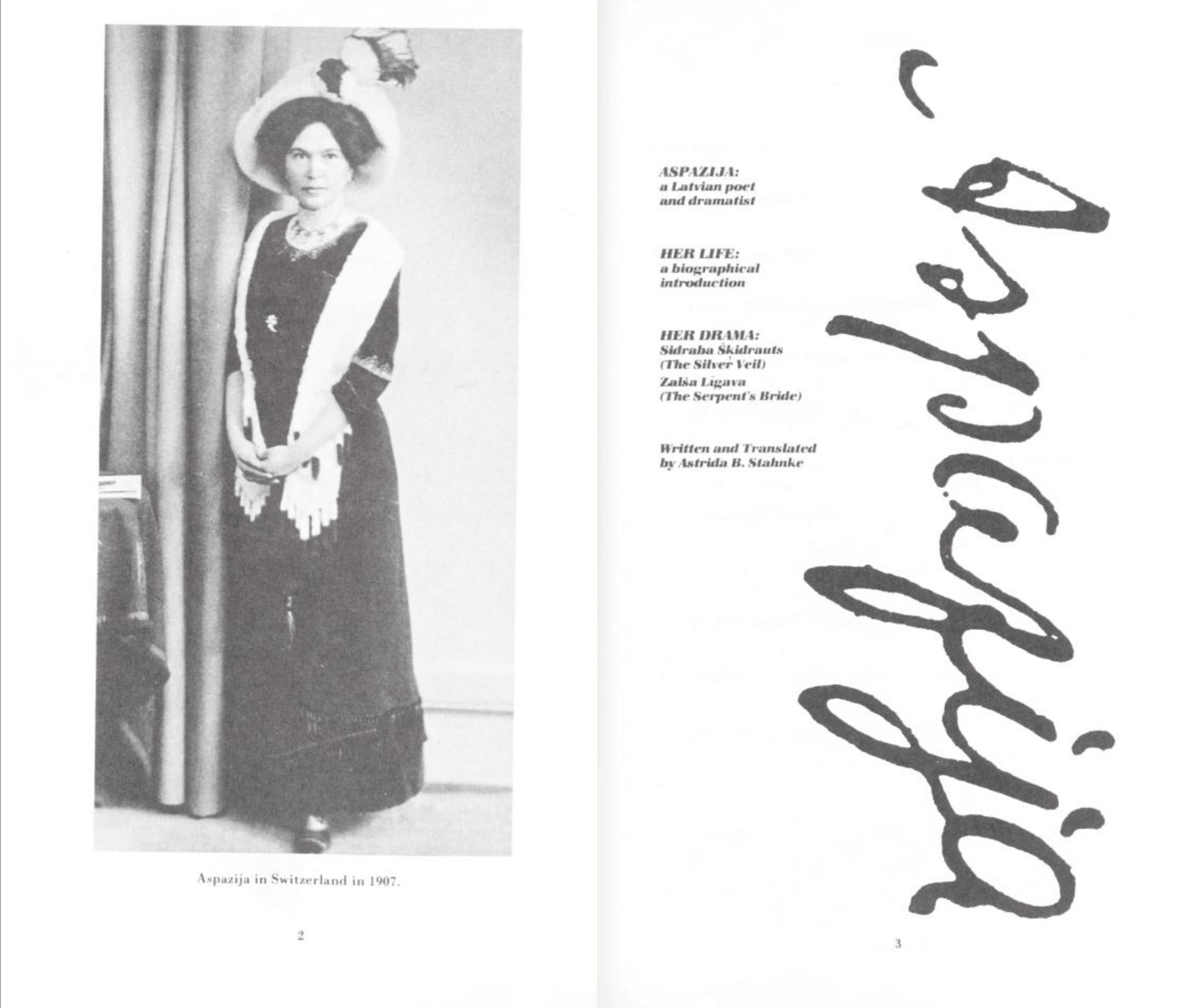

Aspazija and her husband Rainis were revolutionary writers and activists who used their art to protest Russian imperialism. She was imprisoned multiple times and exiled, and was an active member of the feminist movement after World War One. Stiebra's use of Aspazija's poem 'Fairy Tale' (English translation unavailable), is a way of reinforcing the freedom of creativity and Latvian sovereignty in spite of Soviet oppression. Few official translations of Aspazija's work into English have been made, but some information is available in the biography by Astrida B. Stahnke, who translated her plays.

In the film, Stiebra fills the dream-world with flowing water and a gentle breeze, ribbons caught in tree branches float in the air, and winking eyes fill the sky in place of stars, from which the raindrops softly fall. The film follows a young child who journeys with a “story-spirit” and a gentle water sprite across Latvia’s seasons—through spring meadows, Midsummer bonfires, stormy autumn seas, and snowy winter nights.

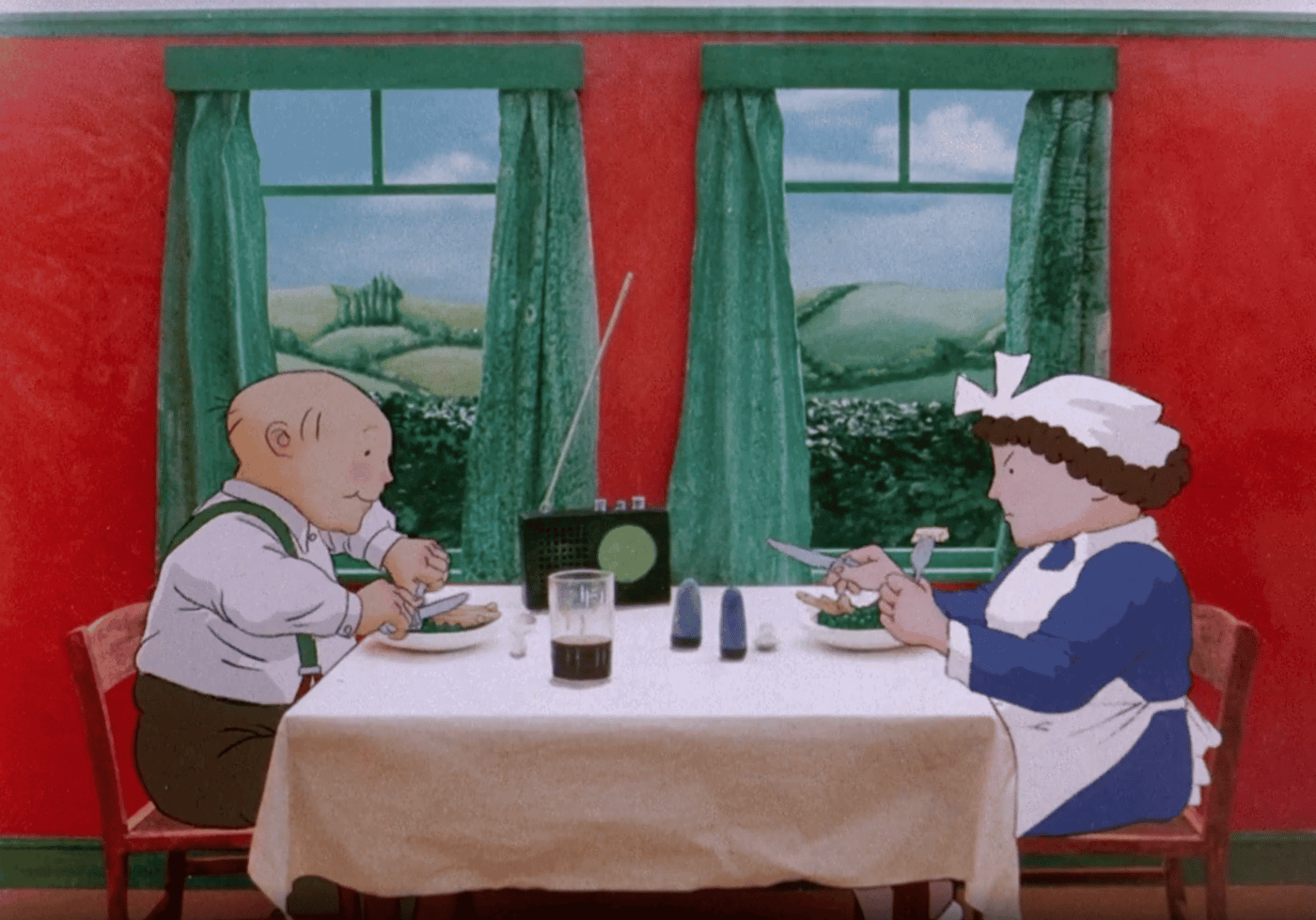

3. Ness and Nessie (1991)

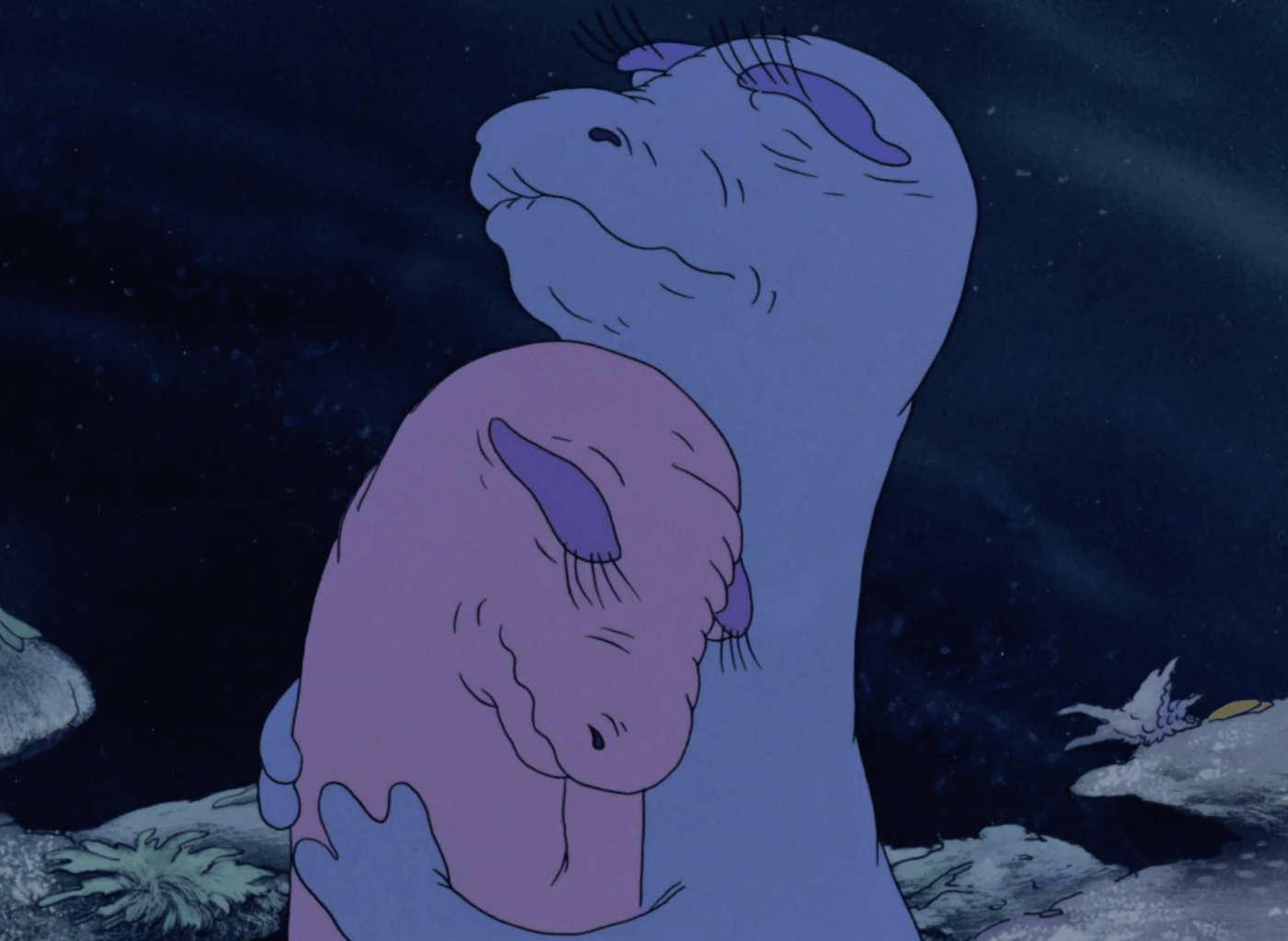

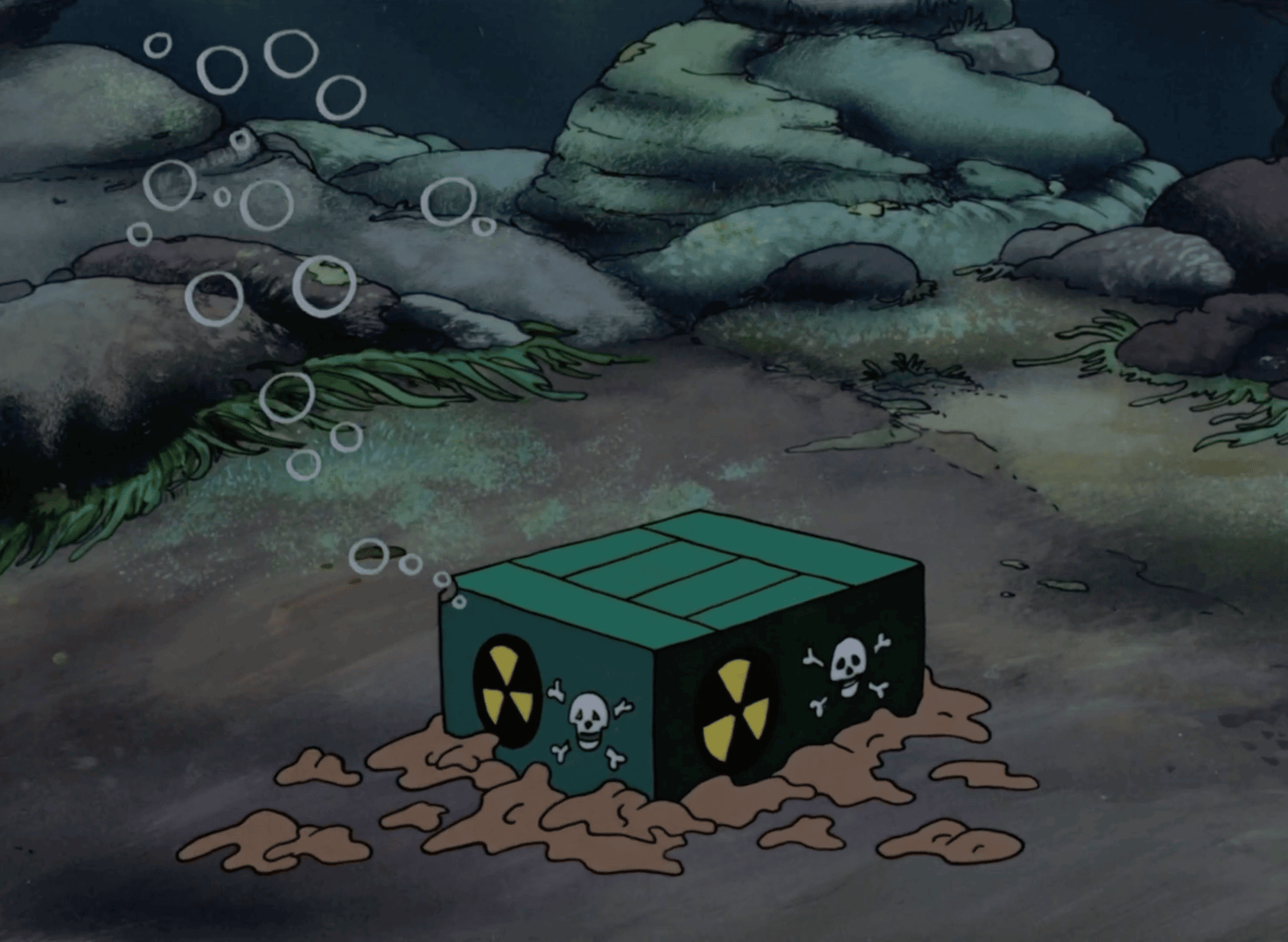

Latvia’s first full-length animated feature, Ness and Nessie told the story of two mythical lake creatures separated across continents who attempt to reunite despite environmental destruction. The film combined Latvian folklore with the legend of the Loch Ness monster, using lush celluloid animation and a score by Zigmārs Liepiņš.

Stiebra's ecological tale arrived after the Chernobyl disaster: a catastrophic 1986 nuclear accident in Soviet Ukraine that released massive radiation, causing widespread health, environmental, and social consequences.

Environmental protests surged across the Soviet Union, and Latvia's activism intertwined with its broader struggle for independence from the Soviet Union. This culminated as a large-scale peaceful protest known as 'The Baltic Way' in 1989 and Latvia forming a Green Party in 1990, which contributed toward the country's reformation when the Cold War ended in 1991. When Ness and Nessie came out that same year, it was well received at home in Latvia, winning the 1993 Lielais Kristaps award and cementing its place as a national milestone.

Symbolism was key for USSR artists, where work was—unsurprisingly—heavily censored. Animators found their way around this, with Stiebra herself noting that, “the language of symbols gained wide use in the Soviet era. Then one had to hide from the censors… maneuver with images and practice flexible thinking”. Even when her films seem purely entertaining, deeper meanings were intentionally embedded. Stiebra's ability to mask bold statements behind childlike imagery allowed her to be subversive without raising too much attention. After Latvia’s independence, Stiebra continued in this vein but with new freedom. In 1991 she co-founded the Dauka studio with her husband Ansis Bērziņš. Dauka became Latvia’s flagship animation studio, producing her later works as well as popular TV shorts like Fantadroms. The 1990s-2000s saw a resurgence in national culture, and Stiebra’s emphasis on Latvian folklore now celebrated rather than censored.

Written by Megan Switzer