This account of the Digital Revolution will be told through the Eternal Family archives, and is thus nowhere near an exhaustive presentation of what is here called ‘Early Technology.’ Please instead consider this a stringing-together of bits and pieces of history, a macaroni necklace of information, rather than a complete info canon. We’ve been gathering playthroughs and demos of old programs, devices, and video archives from the turn of the 21st century, many of which are just hanging out on our platform right now, ready for you to watch. We’re revisiting our interviews with early tech artists Lynn Ochberg (2D, Amiga) and John Sanborn (3D, Laserdisc), and creating a modern TV Guide to what we’re calling technology’s ‘magic’ moment, (1980’s-Y2K). Use this article as a guide to streaming our Early Technology category, with hyperlinks you can revisit later for the full eyes and ears experience :^)

In this guide, we talk about:

- 2D Computer Art & Animation, especially the Commodore Amiga

- 3D Video Art & Studio Software, especially Sony’s Laserdisc

- Computer Ergonomics and the importance of taking frequent, natural breaks from your devices.

We’re contextualizing all this through two major PBS programs: the long-running Computer Chronicles (1984-2002) hosted by Stewart Chiefet, and the single-season Future Quest (1994) hosted by Jeff Goldblum, both great tv shows and true markers of tech history.

It is impossible to predict the future. But let's speculate—what is our world going to be like in 2060 ? In 2094 ? Scaring you yet? How about in 2200? Assuming mankind hasn’t completely destroyed itself and factory reset in outer space, there’s some vague hope that the future could be very exciting. Right? At least, it has been that way in the past. Many sci-fi novelists and PBS show hosts would agree—we’re all fascinated by the future, and for good reason. We just want to know where we’re going!

Progress has always manifested through technology, from stone tools to steam engines to the big cloud in our phones, we humans know where we’re at based on the tools we use. In the 80’s and 90’s, visions of the next gen were popping up everywhere, and by the close of the millennium, technology had utterly transformed both public and private life. By the Y2K, technology had become a central element in homes, institutions, and pop culture worldwide.

Two series in particular stand out to us as prime examples of this tech heyday: Future Quest (1994) hosted by Jeff Goldblum, and Stewart Chiefet’s Computer Chronicles (1984-2002).

Incidentally you can watch em both on Eternal Family in our Early Tech category ;)

Computer Chronicles: The Facts

Computer Chronicles was a top tier TV program, documenting and exploring the personal computer as it grew from its infancy in the early 80s to its rise in the global market at the turn of the 21st century. Running nearly twenty seasons, it’s likely the best archive of digital progress ever televised in the West. Stewart Chiefet has excellent knowledge of the tech world, presenting every device & program to a wide PBS audience, encouraging them to adopt new tech in their own lives. On Stewart Chiefet's show, technology was innovative, exciting, and could be enjoyed by anyone.

This was the salad days of technology; that time is pretty much gone. Through Stewart’s proto-silicon valley energy, we can see the grassroots of today's global tech giants. CC followed Apple, Bell, Atari, Nintendo, Dell, AT&T, Amiga, & hundreds more for over two decades, and always focused on whatever was the present state-of-the-art. It’s a lot to take in, yet somehow incredibly soothing: information comes at you quickly, but the CGI graphics, nostalgic Midi soundboard, and swift interviewing style create the effect of difficulty made easy.

Read an archive of Stewart’s full bio here.

Watch if you like: The Competent Guide, Software & Devices, Technology, Machine Evolution

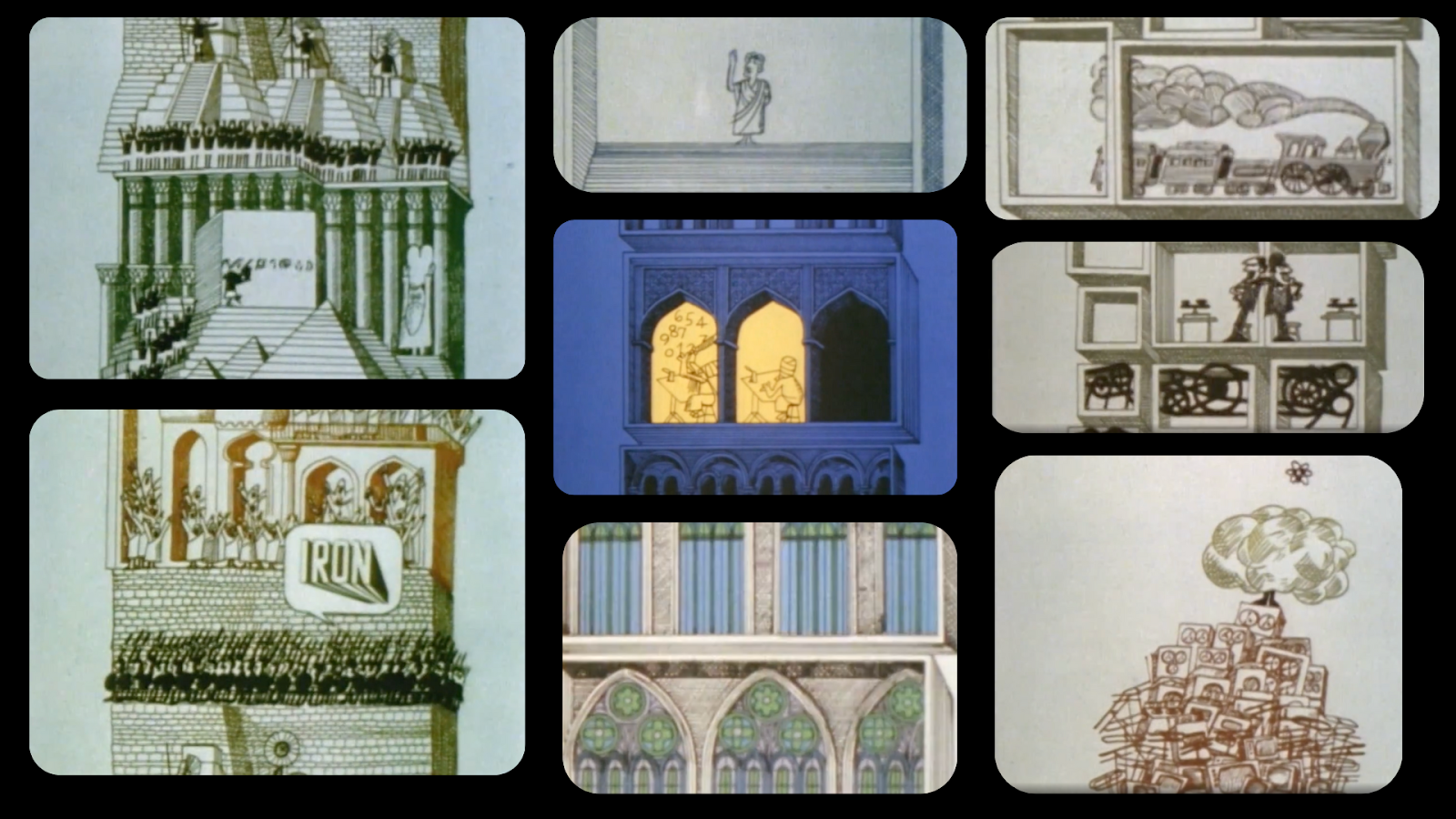

Unlike Computer Chronicles, Future Quest uses comedy, history, speculative fiction, and vox-pop journalism to show the massive cultural changes on the horizon.

Future Quest: The Fictions

We can’t begin to talk about Future Quest without acknowledging the man that is Jeff Goldblum. Unlike Chiefet the tech sage, Goldblum’s character plays the fool, bringing his signature swanky goofball energy to every opening line: Where are we? Do we have other options? And many more important queries. Future Quest looks at progress socially, interviewing writers, comedians, actors, experts, children, and people in the street to better understand the past, the present, and what we can come to expect.

This 1994 mini-series is the perfect counterpoint to CC; it’s all about the social and emotional picture of progress, how people felt at this major crossroads in life & tech. The show is more invested in how progress shapes our reality: stepping outside of the computer environment to understand broader shifts happening in our lives. Future Quest isn’t just about the march of time, but also about strengthening muscles we’ve used in the past, knowing what we carry forward INTO tomorrow from yesterday, and from right now. Or at least, what was ‘right now’ in 1994.

Watch if you like: The Charismatic Guide, Pop Philosophy, Montages, Cultural Evolution

Both will give you: Organized Variety, History, great interviews, visual delights, a sense of contact with the past, laughter, #throwbacks and much more

The Difference: Computer Chronicles looks at technology, Future Quest looks at the society based upon it. They also have totally different approaches to time: CC is in the present, it charts what’s happening NOW, the latest and greatest, while FQ is speculative, fascinated with what might happen, and reminding us to carry on things we’ve done in the past. So to optimize or not to optimize? That is kinda the question,,

It’s been 40 years since Chiefet’s program began, and over 30 for Goldblum’s—inevitably a few things about our mediaverse have changed since the 90’s PBS era. For starters, humans developed streaming platforms, where hundreds of thousands of films and tv shows are available across a variety of internet apps. Streaming soon became a competitive internet market, so platforms began to look for ways to distinguish themselves: some look to the future, recruiting AI studios for high-fidelity original programs, while others define themselves by their libraries, looking into the past, finding the gems hidden away. Our platform, Eternal Family, is a program of the latter, allowing you to access a time capsule of lost and lesser-known media from around the world. Our catalog is always growing, hand-selected by a team of experts just like you :) We gather collections like this Early Tech series and present them here and on our social media, keeping these great works of the past alive and circulating the aether.

Whether it was the latest discoveries or the distant unknown, it was exciting and fun to see the variations on digital progress. The future was promoted as a better, sleeker, more awake and alive world. The digital market was hardly homogenous, you had so many WAYS to experience technology, many niches and skills to pick up. In so many cases, technology seems sufficiently advanced here. No question the gear of today makes life easier and more entertaining, but when I sit down and watch these episodes, listen to their conversations, it’s easy to wonder: have we optimized the magic out of our technology? Let’s take a look at the old home studio and see for ourselves.

The Home Studio: 2D Computer Art and the Commodore Amiga

Commodore Amiga

When the Commodore Amiga showed up in the mid-1980s it was a home computer that felt like it came from the future. It contained custom chips for graphics, animation, and audio in hardware, which meant smooth multitasking, bright color displays, and surprisingly rich sound. From the beginning, AMIGA set the standard for every element of computer design. This machine was a major step forward in computer design, and represents a kind of ‘golden age’ of progress in the home studio.

Programs like Deluxe Paint gave people pixel-level control, easy palette editing, and frame-by-frame animation tools that had never been available on a home computer before. Designers and hobbyists suddenly had access to a digital workspace that pushed the industry forward—other companies had to scramble to catch up, borrowing its interface ideas and creative workflows. The Amiga essentially turned the home computer into a full creative studio, reshaping everything from game art to early CGI experiments and giving a generation of artists their first real chance to build work directly on-screen.

Even with all that power, Commodore’s dedication to the home computer setup presented more marketing challenges than they could beat. The company went bankrupt in 1994, leaving the Amiga’s real potential only partially tapped. For many, including home animator Lynn Ochberg {up next} , the loss of the Amiga was a real tragedy.

Turkish character sheet for Street Fighter II for Amiga Games

To see the Commodore in action, visit Computer Chronicles episodes: Amiga & Atari, The New Amigas, and Amiga 3000 now on Eternal.

Stills from Art Dabbler, Amiga Handbooks an AMIGA Colour palette of ‘Colours Not Found in Nature’

In looking at the wonders of Amiga design, we at Eternal can’t go without mentioning the animated series by Lynn Ochberg: The Films of Nanny Lynn. Initially a homemade film project, this series was lost and later rediscovered when bootlegged VHS tapes surfaced at a Michigan video store. Soon after, the tapes built a cult following in underground film and noise circles, tracing back to surprising origins: the home studio of a loving grandmother.

We spoke with Lynn, and are ready to set the record straight. These films were made using ONLY Deluxe Paint 2 and 3 on a Commodore Amiga. All effects, techniques, and clip art graphics were single-handedly implemented by Lynn using this setup. No AI, and for that matter, no internet was involved in the creation of these animations.

Stills from The Story of Srebrenica, Jake and Dylan Vacuum the Universe, The Alphabet Movie, and the mastermind herself Lynn via zoom from her beach house in Florida. Love all these genuine gems!

EF: Your animations have such a distinct character and look. What influenced your digital style?

Lynn: The digital style was very much a result of the limits of the apps on the Amiga. It's a matter of drawing, pixel by pixel, and then using math to move things around. In that app, you'd just put the mathematical equation for what you wanted your object to do, like go from one corner to the other corner, around and around, it was all just simple math. It allowed me to just type x + 3 or whatever it was to make it move, like simple geometry.`

EF: What do you hope people take away from your films?

Lynn: I just hope they show them to their kids, you know, because they were all done for the kids. Of course they're old fashioned now, so the historical references might not be understood. But kids still love dinosaurs.

[Watch the Films of Nanny Lynn]

Another interesting example of a 2D animation program is seen in Michaël Gaumnitz’s 1987 short animation compliation: FEMMES, all hand illustrated on a graphic tablet. The artist styles computer graphics in the fauvist tradition, using the recording features of the Graph 8 program to create animations that were at once handmade and computer-generated.

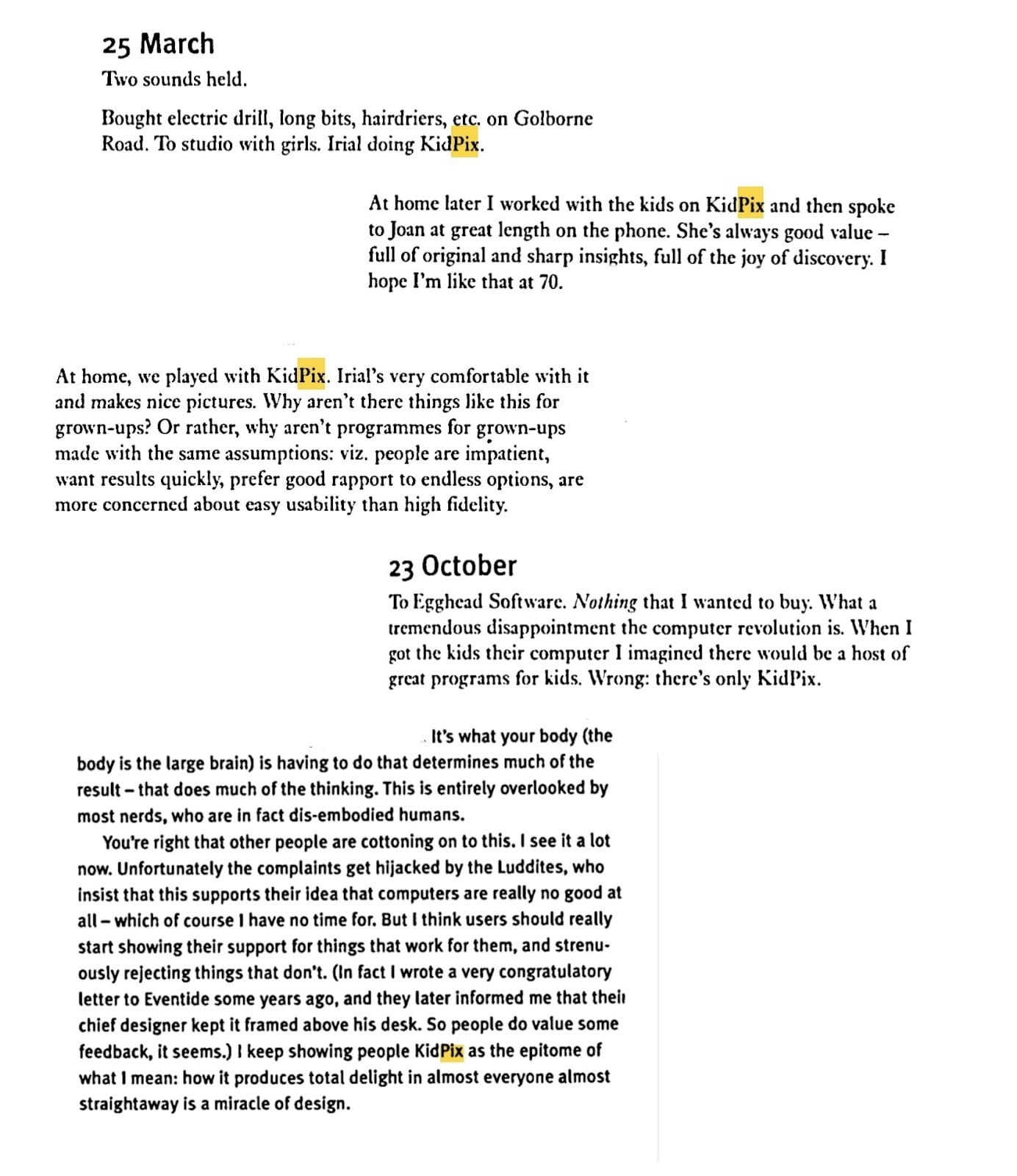

Every time Brian Eno mentioned KidPix in his diaries

Programs like Deluxe Paint, Art Dabbler, KidPix, and many other paint programs were a huge hit in the home setup partly because they were designed with kids in mind. For a lot of us, computer art packages were our first memories of the computers: software developers at the time understood this and wanted to create fun, creative ways for kids to learn how to use the computer. When these programs grew obsolete, a certain magic of the computer died with them.

Tolls for the Serious Artist: 3D Graphics and Sony Laserdisc

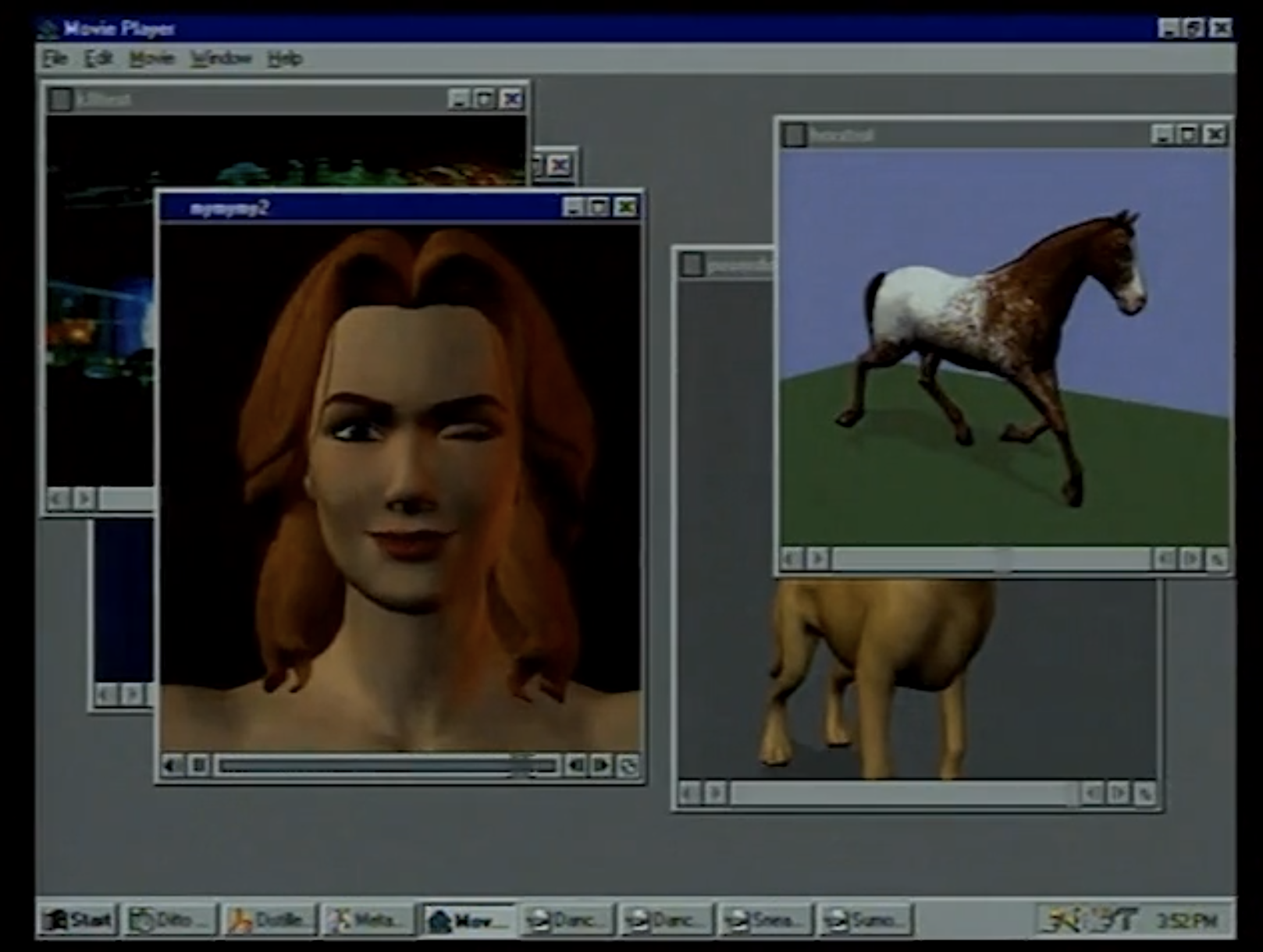

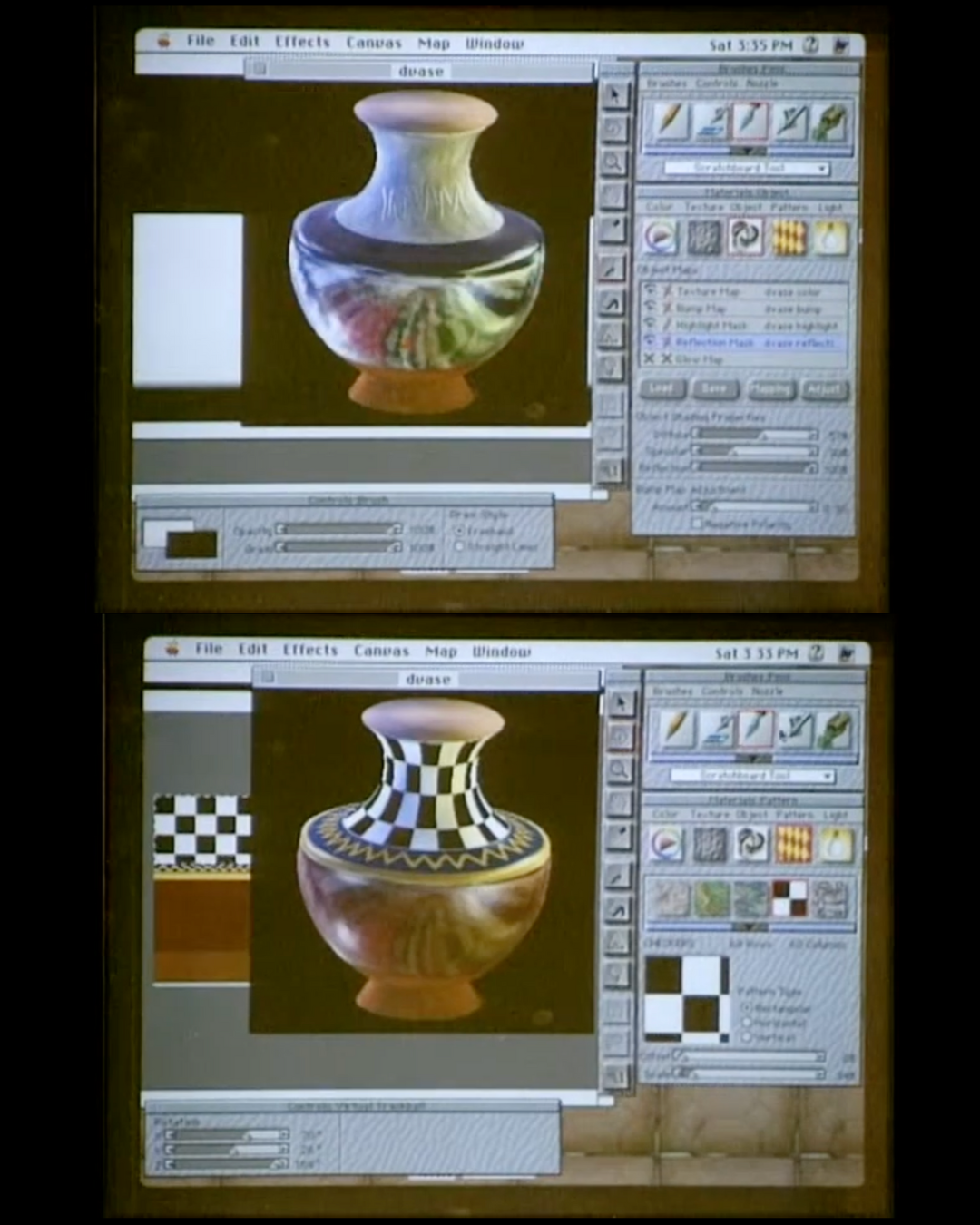

3D became the CGI for artists, and for the discerning PC user. 3D software was most popular among graphic designers and other computer artists, who used the systems to create virtual galleries, performance artwork, and some crazy beautiful looking graphics. It was all deeply interactive; YOUR execution of YOUR OWN ideas was central to the image-creation. Back then, ‘Computer Art’ was art you make using a computer, unlike now, where the machine can have a lot more decision making power, if you’re into that kinda thing. If you want to learn more about the state of the 3D artworld circa 1997, let the real ones explain it to you on this episode of the computer chronicles:

Computer Art

In contrast to the home computer, by 1990, 3D rendering debuted primarily for serious artists and studios worldwide. Leaders in the field were often based in Japan, with particular motion coming out from Sony. LaserDisc: with its unusually high image fidelity and imaginative 3D modeling, became a significant backbone for early CGI film and workflows. LaserDisc found its way into arcades, film labs, and animation studios years before consumer hardware (like our friend the Commodore) could possibly keep up.

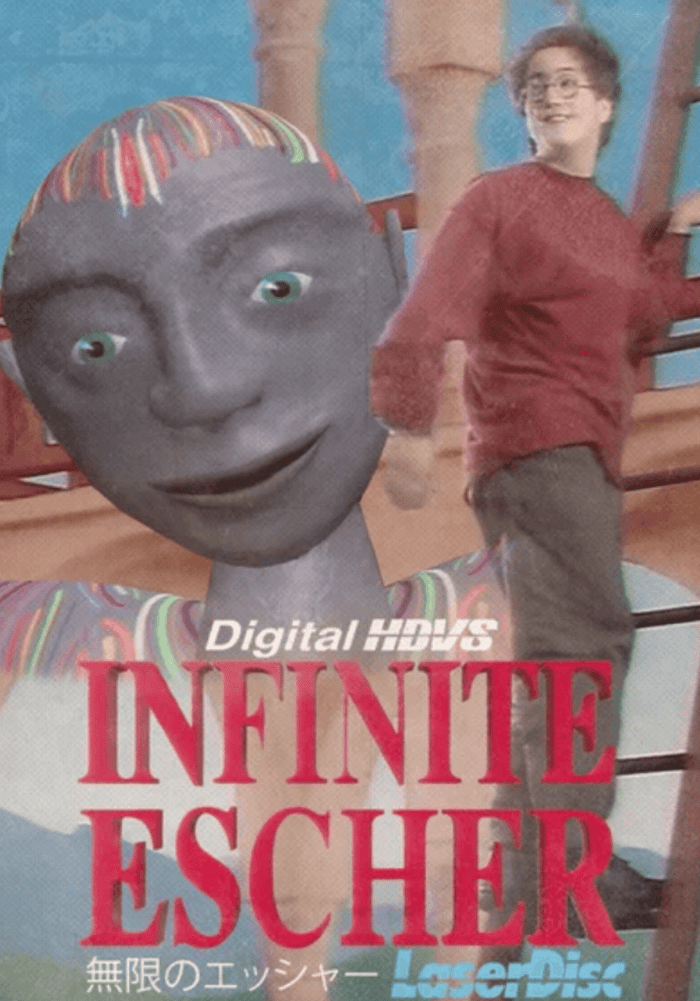

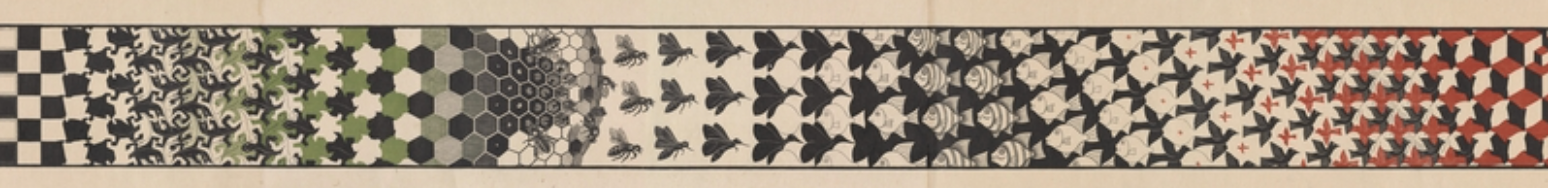

Japanese developers and artists embraced this format as a bridge between disciplines, using CGI to elevate everything from arcade cinematics, industrial design, and experimental animation. We saw this with the 2D world, but on a smaller, more design-oriented level. With the advent of 3D CGI, computer companies were trying to establish these tools as something of genuine art. In 1990, Sony released Infinite Escher, a film inspired by the great modern artist, with art direction by Nam June Paik and score by Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Part new media showcase, part modern art fantasy, Infinite Escher unfolds like a technologized Through the Looking-Glass: an unnamed boy (Sean Ono-Lennon) sketches quietly, disconnected from the world. He looks into a crystal ball, and the boundaries between reason and imagination dissolve.

Last summer, we spoke with John Sanborn, who co-directed the film with Dean Winkler and Mary Perillo. John discussed the creative process, artistic influences, and environment design in their then-groundbreaking tech showcase.

L-R: Soundtrack by Ryuichi Sakamoto (cover art by Floyd Gillis), Nam June Paik, Self Portrait, 1989; Sean Ono-Lennon as ‘The Boy” with Laserdisc’s Bulge effect re: the original by Escher

Eternal Family: So, how did the concept for Infinite Escher come together?

JS: There was a great celebration in the 80’s that everything was possible. Sony was developing their own HD systems, so they wanted demos to show off the look, and what could be done with their graphics. At the time, it was only 780p, nothing like the HD we have today. [...] I can’t remember if the call came from Sony themselves or [Nam June] Paik, but they wanted to use CGI as a way of visualizing the impact Escher had on the world, bringing the fantasia of that style into video art.

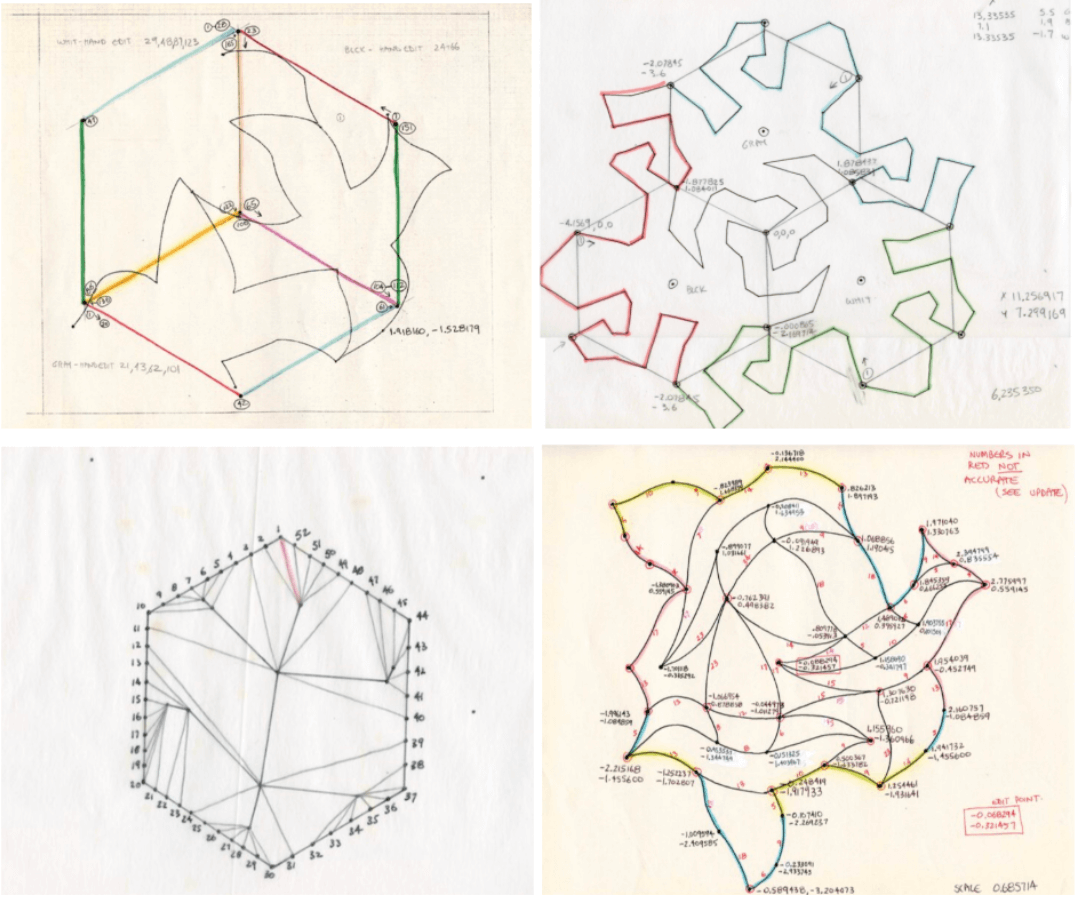

JS: We tried to include as many works as possible. Escher compounded and compacted the stuff of life, whether in a globe or a panoramic view. Tessellations, geometry, the idea that something can be one way at first and be very different the next time you look at it … all of these things were a big part of how the film came together.

For more info about animating escher, visit animator Floyd Gillis’ website https://www.floydgillis.com/Comm/PostPerfect/

Beny and The Mind’s Eye:

Another example of great 3D innovation we’ve got here on Eternal is Beny Tchaicovsky, creator of The Morning Star Trilogy. Unlike the 2D world which looked at more traditional painting, 3D artists were inspired by modern art and surrealism. Considered one of the great innovators of 3D video art, Beny set up shop in California in the early ‘90s, already an established artist, founding Zoe Productions in Fairfax in 1993. There he began experimenting with computer-generated imagery—not for commercial purposes but as a challenging visionary art form. He contributed to LaserDisc compilations like The Gate to the Mind’s Eye (1994) and Odyssey into the Mind’s Eye (1996) with segments such as Quantum Mechanics, Modus Vivendi, Delirium Tremendus, and House of Mirrors. He called his style Esoteric Realism, using 3D as a tool for spiritual exploration and new creative freedom.

View the complete Mind’s Eye collection here:

In 1997, he released his first full-length feature, Cyberscape: A Computer Animation Vision, using mythology and symbolism to trace humanity's journey from Eden to quantum mechanics. His later projects included the Morning Star Trilogy—The Call, Caught Between Worlds, and Dimensional Connections (all 2001). These three are available to watch on Eternal Family.

For more information, visit Beny's personal website here:

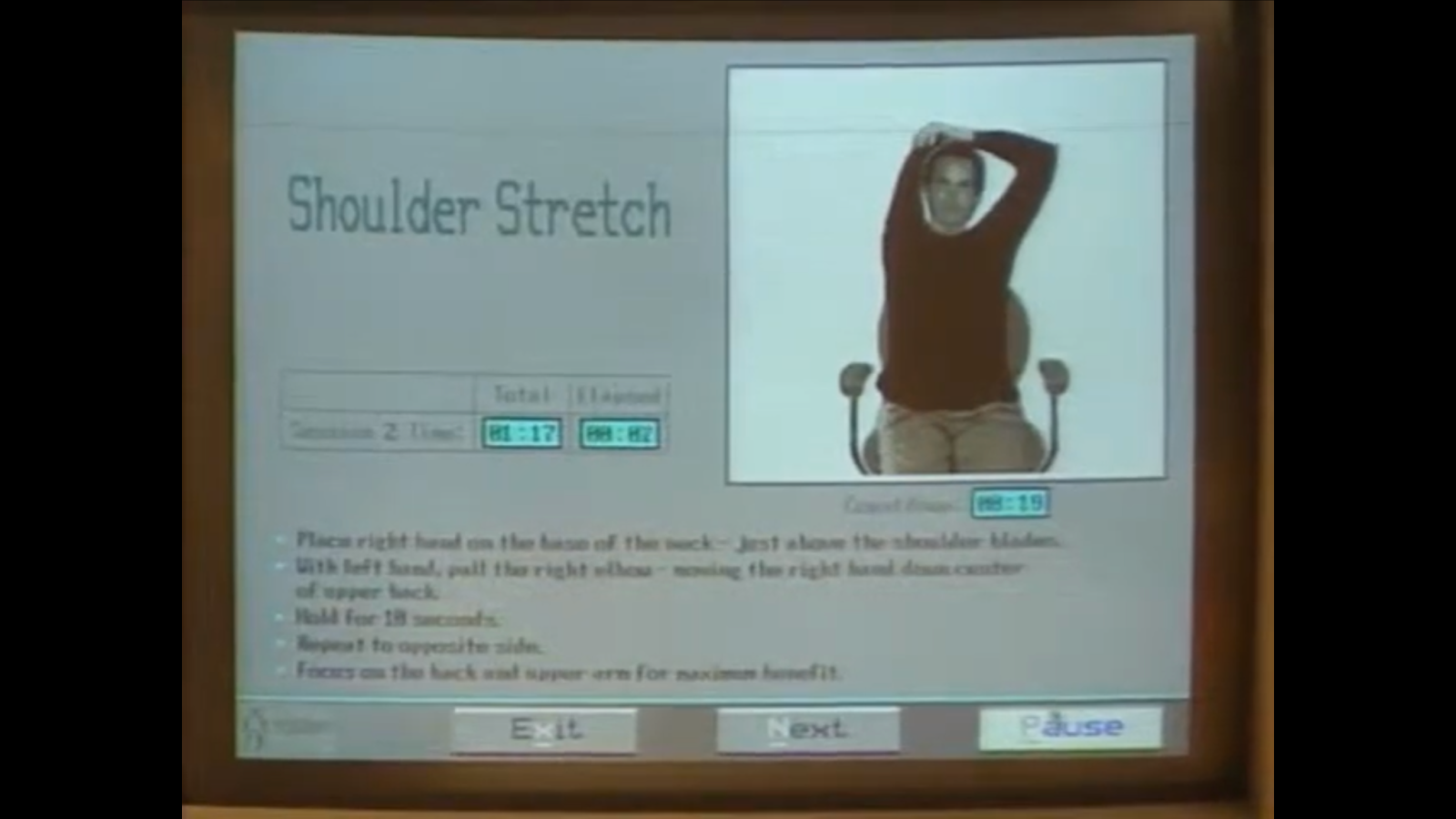

(((((Quick reminder to give yourself consistent, natural breaks from your phone/computer, and watch out for your health on these screens and at your desks in the day or night time. See how they handled Computer Ergonomics in 1993 on this episode of the Computer Chronicles. And please, stretch!)))

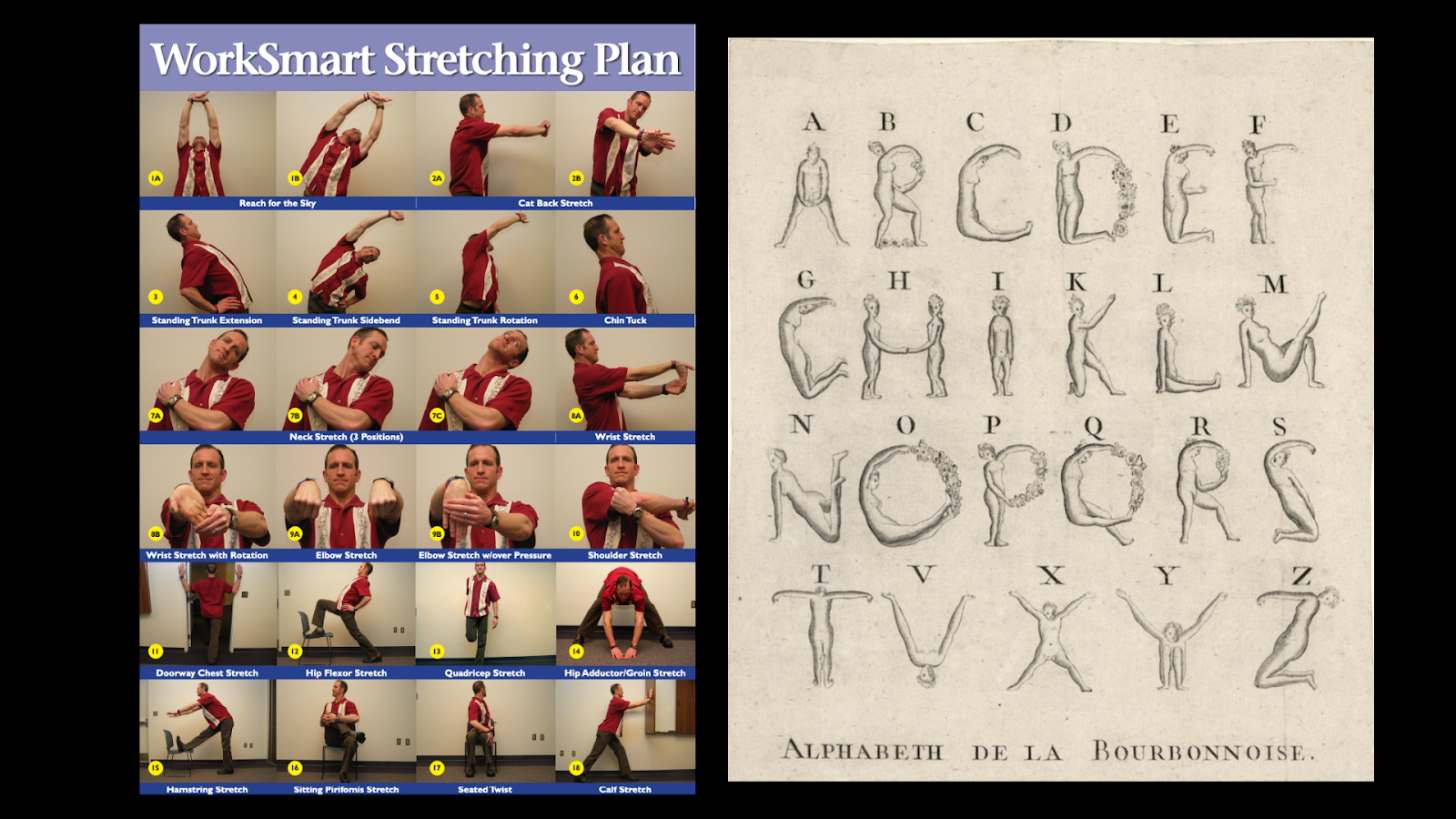

You can rely on the Worksmarter (1993) routine to survive the trenches of the desktop, or shake it up with Alphabeth de la Bourbonnoise (1789), moves for the expressive typist.

Back to it! Wrapping up I swear!

In the age of CC and Future Quest, the novelty and variety of digital experiences was so abundant. This idea of the future was continually presented as a better, sleeker, more awake and alive world. In so many cases of this period, technology seems to be sufficiently advanced. It seems incredible. We might have been fine to have stopped there! Yet of course, inevitably, we did not. We could not. It’s the nature of time that we move ahead; in the future things always phase out and new things take their place, it’s up to us what that actually means. Sure, the future has pulled us into some interesting times, but when I sit down and watch these tapes I just keep thinking: have we lost the magic? I’ll hazard a yes, but I am not a scientist. I’m just having a look at the information age from the distance of now: 2026, taking stock of what followed us out of the Y2K and what we left behind.

Please enjoy the complete Early Tech Collection on Eternal Family, and let us know what you think the next category feature should be 😄

This article is published in memory of Stewart Chiefet (1938-2025)