If you grew up in front of the television in the 1980s, chances are you’ve experienced it: that eerie, half-memory of a film you were sure you saw, but could never quite place again. The kind of thing that made you wonder, Did I dream that? For a certain generation, that half-remembered fever dream is The Peanut Butter Solution (1985).

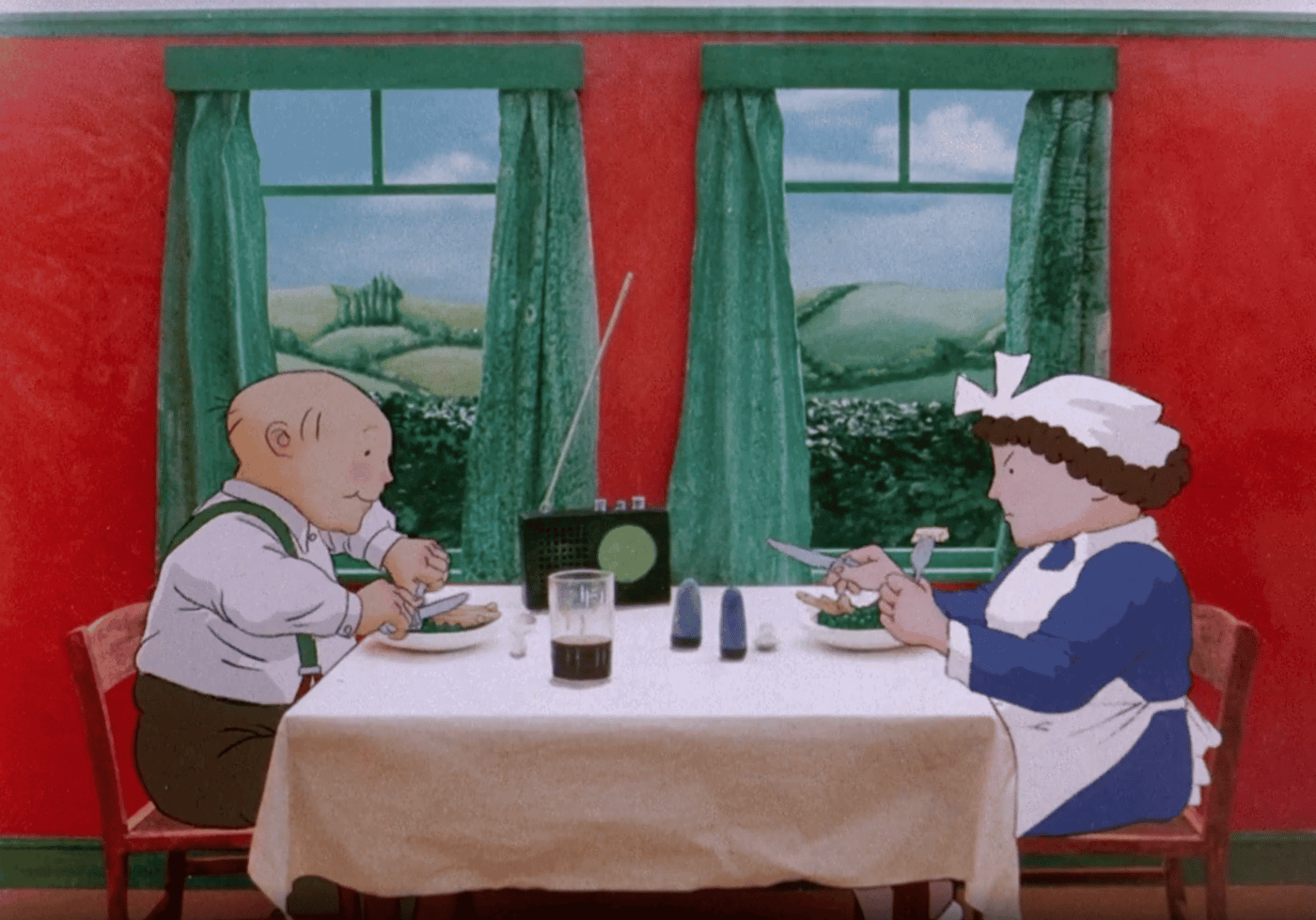

The details are hard to forget: a bald kid, a pair of ghosts, a sweatshop full of children forced to make paintbrushes out of human hair, and a magic potion laced with deliciously smooth and creamy Skippy brand peanut butter. (Chunky one not that smooth, still delicious.)

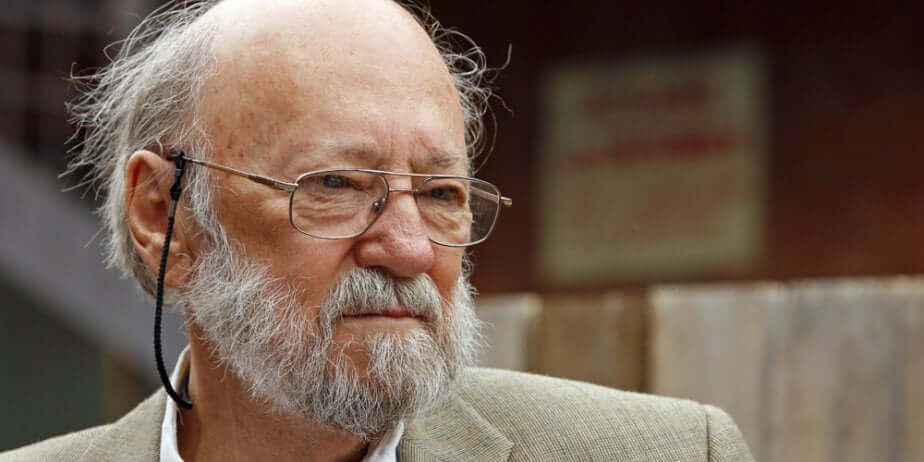

For years it seemed to many like maybe it was just a bad dream but now it’s clear: The Peanut Butter Solution was very real. And it’s the strangest entry in Tales for All, a series of fantastical, sometimes confounding children’s films produced by French-Canadian visionary Rock Demers (1933–2021).

Rock Demers: From Cinephile to Producer

A lifelong cinephile, Demers absorbed films from every country he passed through as a young man. During a nearly two-year journey from Paris to Tokyo, he became especially captivated by works created for children.

Upon returning to Montreal, he worked as a programmer for Loews Theatre. On weekend afternoons he drew thousands of children to screenings of the foreign films that had so deeply impressed him abroad. Soon thereafter, he launched his own distribution company, Faroun Films, acquiring the rights to children’s cinema as well as arthouse and experimental works. “My hobby [the distribution company] developed so fast that two years later I had to choose between it and my regular job. I chose my hobby, of course.”

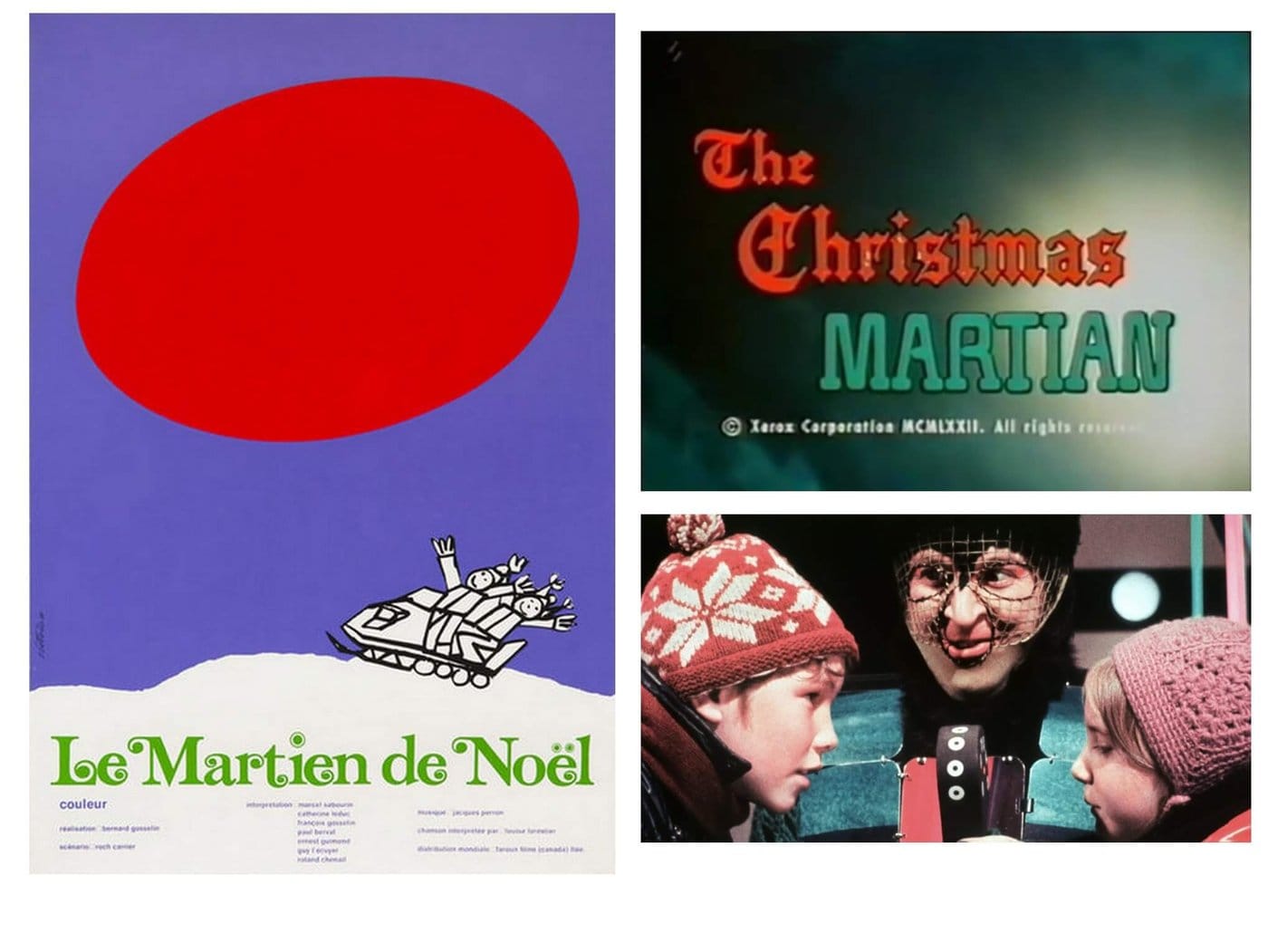

In 1967, Telefilm Canada was founded as a crown corporation to support and promote Canadian screen-based content. Among its earliest investments was Le Martien de Noël (1971), a whimsical tale about Poo Flower, an alien exploring a snowy Quebec village. Demers initially funded the project himself, but when his resources ran out before production wrapped, he turned to Telefilm for help. The completed film became one of Canada’s first feature length children’s films—and the first to be distributed internationally, reaching more than forty countries. This success marked Demers’ transition from distributor to producer and launched his longstanding relationship with Telefilm.

Tales For All

In 1979, Demers founded Les Productions La Fête with the goal of producing nine children’s films. Moved by an article on child-suicide rates, he envisioned a series—Tales for All—built around a single message: “Life is difficult but… it is worthwhile.” Determined to create films that were both fantastical and challenging, he began with The Dog Who Stopped the War (1984). In it, the titular dog (major spoiler alert) dies, serving as a metaphor for civilian casualties.

Other notable entries in the series include The Great Land of Small (1986), which features a benevolent god named Slimo; Bach and Broccoli, which features a dead beat dad and a skunk named Broccoli, (1986); Tommy Tricker and the Stamp Traveller (1988), which showcases the vocal talents of a pre-pubescent Rufus Wainwright; and Tadpole and the Whale (1988), which is essentially a proto-Free Willy.

But the second instalment would prove the most unforgettable: The Peanut Butter Solution.

The Peanut Butter Solution

For this project, Demers partnered with Australian-Canadian filmmaker Michael Rubbo, best known for his work as a documentary director for the National Film Board of Canada. Rubbo, a father of two, based the story on a bedtime tale he had told his eldest son, initially titled Michael’s Fright. Thirteen drafts later—developed with input from Czech filmmaker Vojtěch Jasný, mentor to Miloš Forman and director of The Cassandra Cat—the story became the haunting, absurd, and oddly endearing film we know today.

The plot is as bizarre as its reputation suggests. Young Michael is so horrified by the discovery of the charred remains of two houseless individuals that he loses all his hair. The ghosts of the deceased— unbothered by their fiery demise—offer him a cure for “baldness from fright”: a magical hair-growth potion whose key ingredient is Skippy peanut butter. (A delectable culinary choice, if not exactly dermatologist-approved.)

As Demers later explained:

“Of course we didn’t want to label it as a horror film for children. We think the film is very playful, has a lot of humour, and we also thought that kids like to be afraid. What we wanted to do was have a gently frightening film. And within that we wanted to say, ‘When you are afraid of something, try to find out why that thing has frightened you. And if you find out you will realize most of the time that it was not that frightening.’ We realize that for kids under eight, it might have been a little… tough. But I have asked many of them if it has bothered them for a long time and I’ve found most of them have said no. They said, ‘We have had some nightmares but we are over it, and now we would like to watch it again.’”

The film went on to become the most famous entry in Tales for All. Distributed theatrically and later on VHS in the United States by New World Cinema, it also played frequently on HBO. Its surreal imagery—pubic hair sprouting from the bottom of a child’s pants, a gum-caked wig being violently ripped off, child abduction, and a sweatshop of enslaved children—cemented its place as one of the strangest and most disturbing children’s films of the 1980s, a decade not exactly lacking in strange and disturbing children’s films.

Music, Marketing, and Peanut Butter

One of the film’s most unexpected collaborators was Céline Dion, who at just seventeen contributed two original songs for the soundtrack— the first English-language recordings of her career. The score itself, composed by Lewis Furey, blended 1980s pop with cabaret. “He seemed like the kind of producer I’d like to work with,” Furey said of Demers. “He didn’t have that appearance of a lot of producers at the time who were very slick. There was nothing slick about him.”

The production, however, faced financial hurdles. After the 35mm film was transferred to video for editing and then back to film for theatrical release, little money remained for marketing. Salvation came in the form of peanut butter giant Skippy (delectable to say the least), which provided $100,000 in promotional support. This included traditional advertising as well as a novelization of the film and a storybook-style album and cassette featuring Dion’s songs and a basic plot narration by the film’s young star, Matthew Mackay.

Legacy

“I’ve done a lot of things,” Demers once reflected, “but the Tales for All are the most important in my life.”

And if The Peanut Butter Solution continues to linger in viewers’ memories as a strange blend of childhood nightmare and cult curiosity, that is perhaps the highest testament to Demers’ peculiar genius: he made children’s films that refused to be forgotten, and for some that’s because the kids grew really long pubes out their pants and for others that’s because the stories were truly affecting, one-of-a-kind works of art.

Watch The Peanut Butter Solution now on Eternal.tv

Written by Matt Prins