Peter Greenaway was a painter before he started making films. He saw cinema as a painter's medium, and transposed that belief in every single frame. Drowning by Numbers is the kind of film better referred to as a picture; the images of this film are really the heart and soul of it. Everything else is totally fixed.

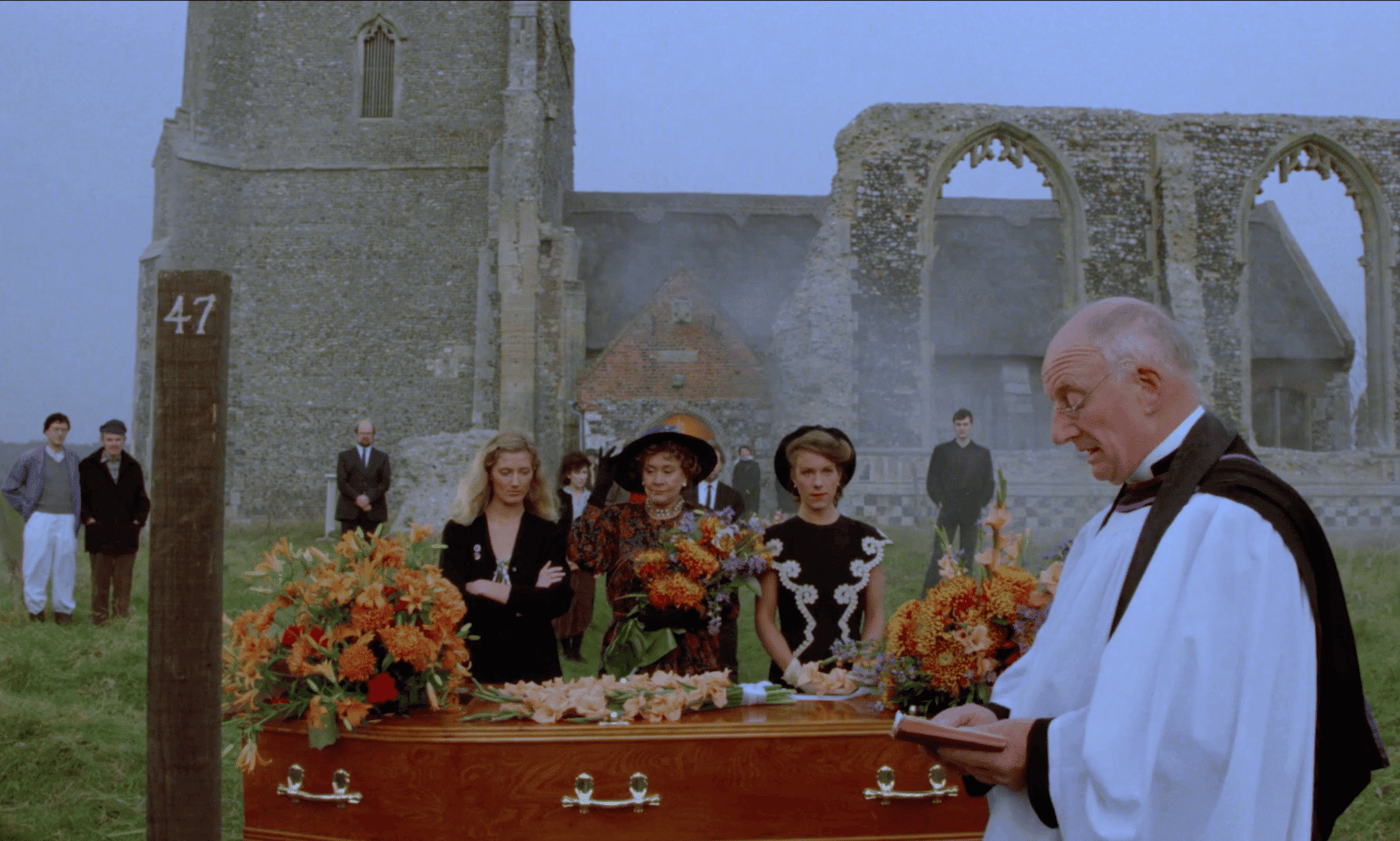

The film unfolds through games, the primary game being a number count, with visual and verbal counting from 1 to 100 hidden throughout. It features a constant series of invented games played by children and adults alike, and a tightly controlled aesthetic that recalls children's stories, classical music, and centuries of great painting.

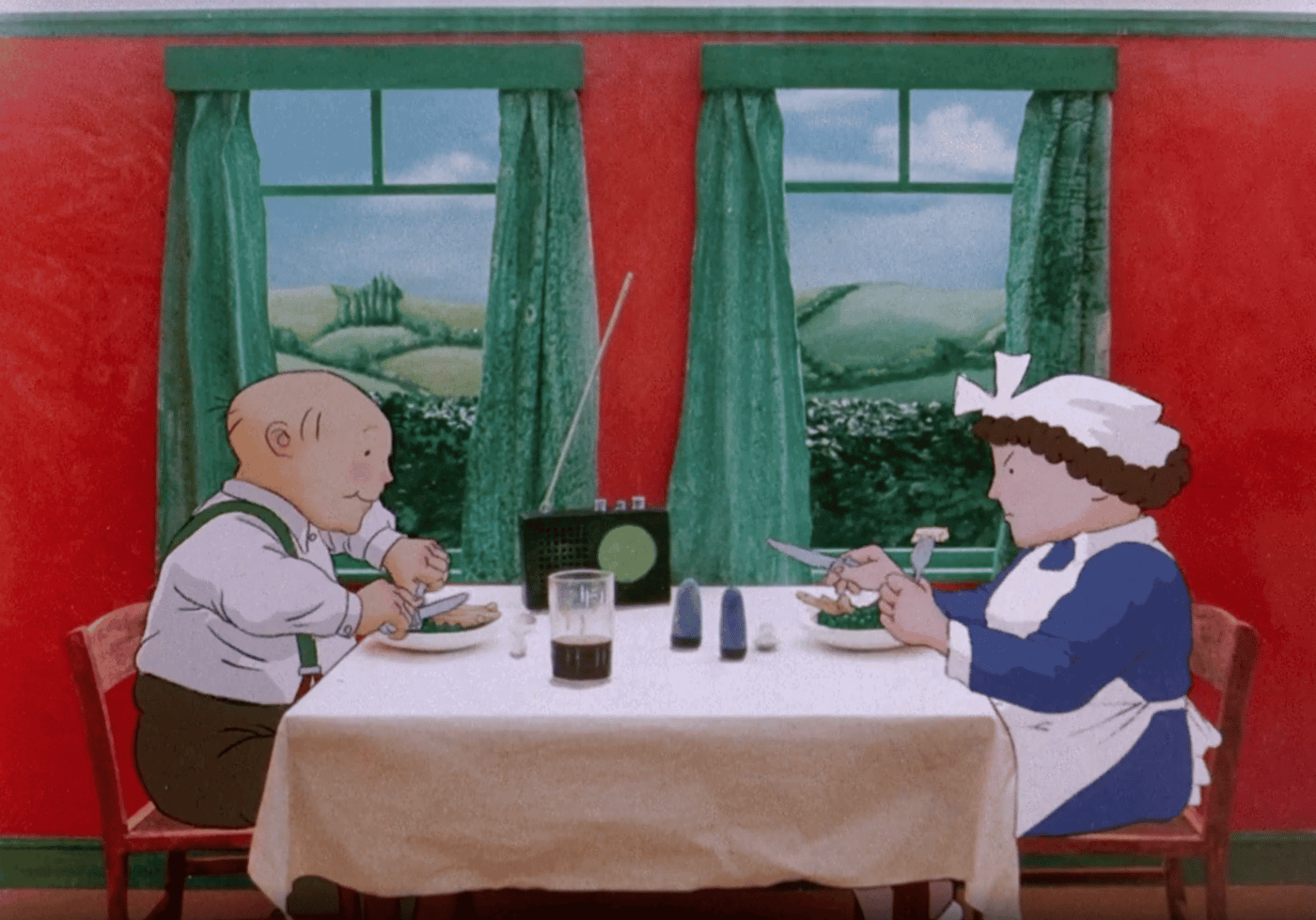

The narrative is simple: an adaptation of the children’s fable The Three Billy Goats Gruff. Three women manipulate their local coroner into covering up their murders so they can cross into the greener pastures of life without their husbands. The drownings are presented in a wry, half-comical, increasingly predictable manner, and when coupled with the picture-perfect framing, the world of the film appears to be an imaginary one.

Like the billy goats, Drowning by Numbers is a film of threes: three matricides, three autopsies, three funerals, three reckonings, and three women who share the same name: Cissie Colpitts. Their story is three tales in one: a long slow spiral uncoiling to its end. And so, like a spiral, we soon begin to pass the same marks and suspect where things are going. From the beginning, Drowning by Numbers is a highly structured and deeply artificial narrative: once we get to 100, the story will have met its quota, and the film is over.

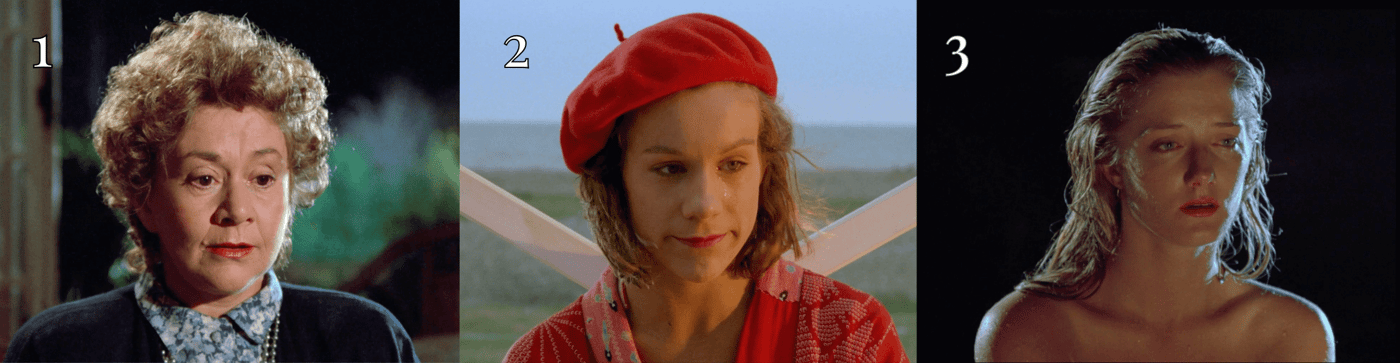

The Three Cissie Colpitts

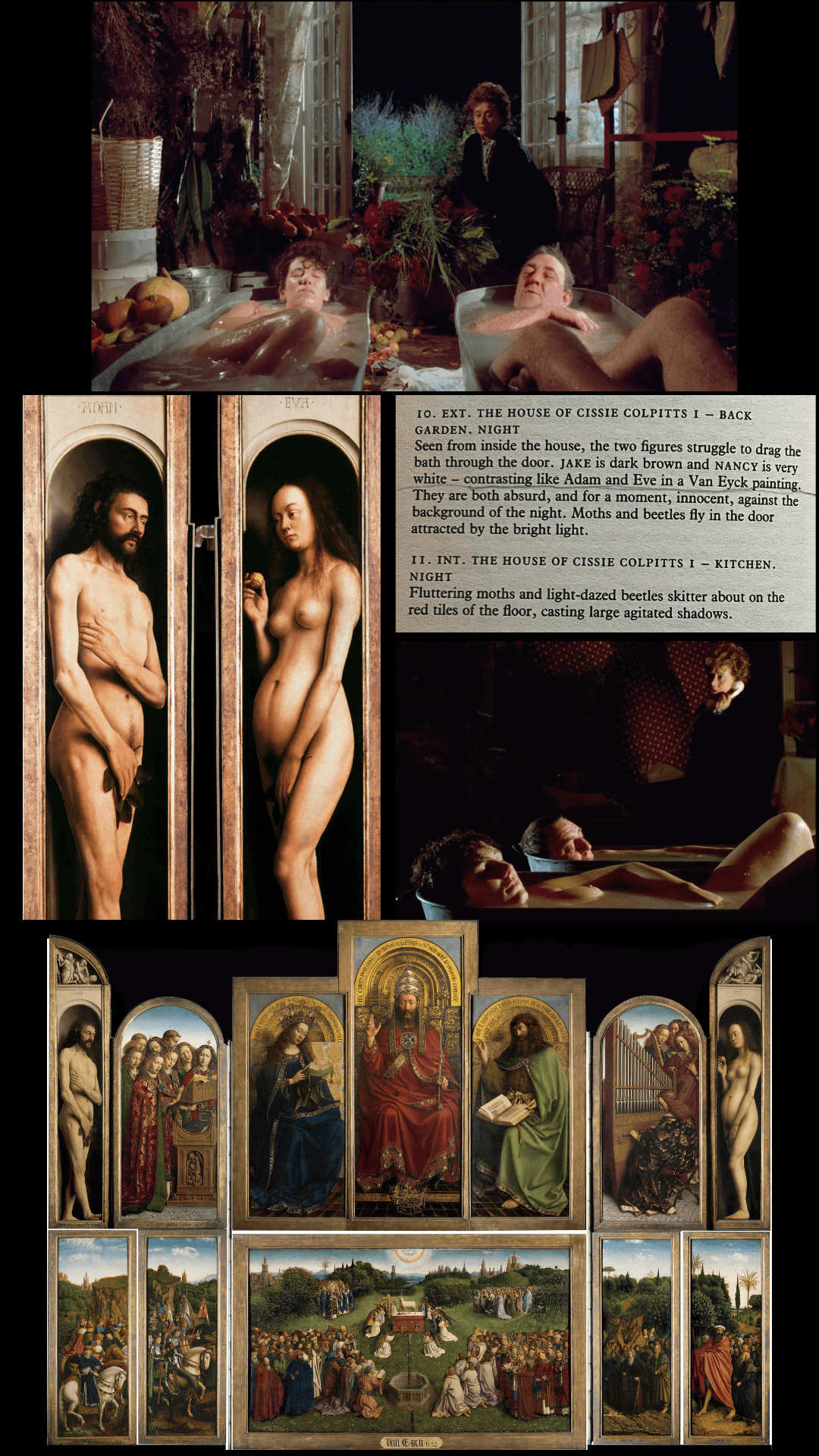

"Cissie Colpitts has a longer history still." Greenaway writes: "As a single entity and not three people, she appeared in 1976 as a companion to Tulse Luper in Vertical Features Remake and had a biography all to herself in the 1978 version of The Falls. In Drowning by Numbers she is three people—three generations of solidarity taking action against marital dissatisfaction."

When casting the film, Greenaway chose to work with stage actors—classically trained players who embodied stiff, half-eccentric English stereotypes. Of the three leading ladies, he later remarked that: “these three extraordinary ladies have all got, I think, a reputation for being associated very much with British theatre, so they come along dragging their cultural baggage with them [...] I think that sort of artificiality is built into their dialogue and essentially built into their performance.” This casting choice was one of many layers of artifice Greenaway applies; the film thoroughly acknowledges itself as a film, imparting more of a staged, storybook quality than an immersive experience.

There is no suspense here. Each dramatic development is heavily anticipated in the dialogue, and the structure makes itself plain from the beginning: a counting game. The numeric arc continually reminds us that this isn't real, this is just a film: we know what’s going to happen and how it’s going to end, so we can all but look past the story and read the images instead.

Artificial as the story may be, the film isn't without emotion. Where love is lacking between the adults in the film, it seems to be delegated to the boy, Smut, who pursues the 'Skipping Girl' to his own detriment. Most of the deaths in the film come as no surprise, and feel almost comedic, but the storyline of these two creates some counterpoint.

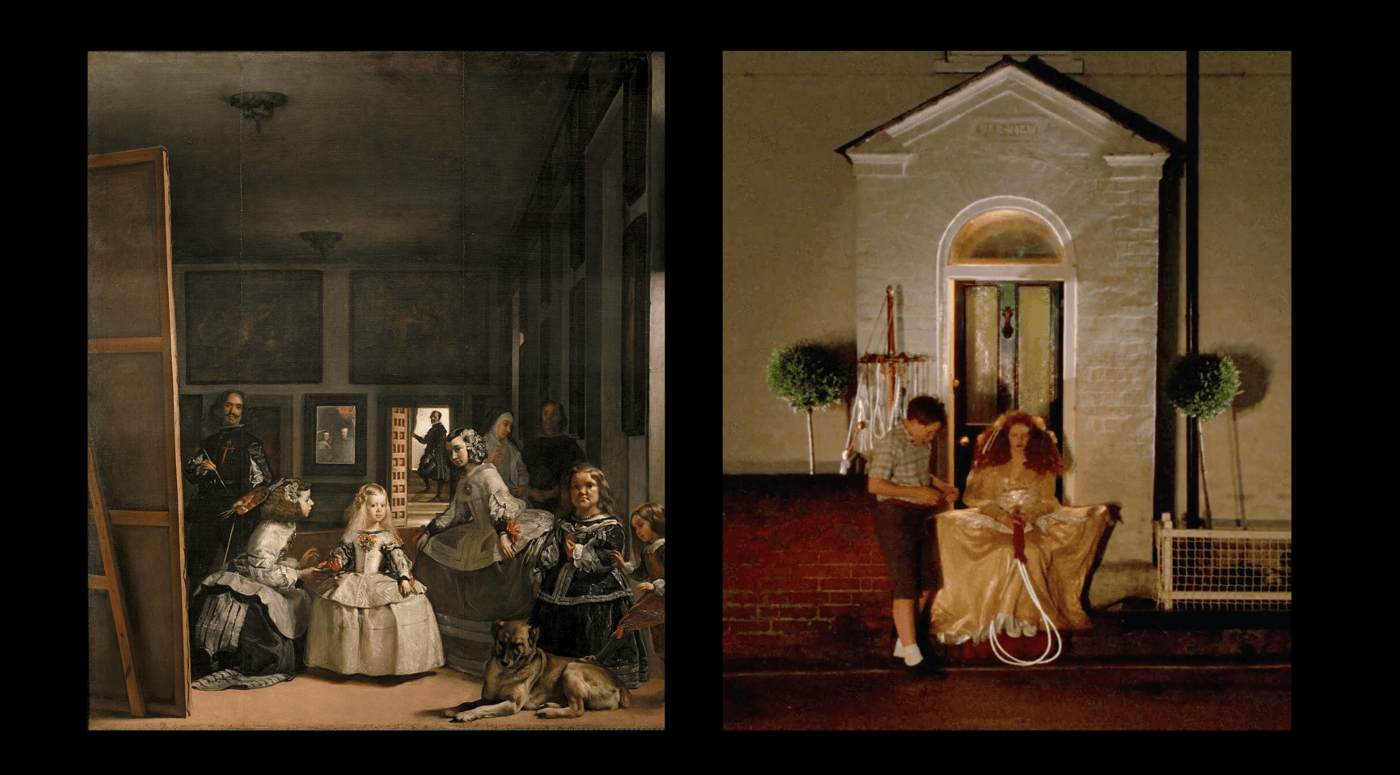

Like Velasquez's Margarita, Greenaway's girl doesn't understand how influential she actually is, and innocuously drives Smut to drastic measures. Numerous deaths occur, but their fates are the only tragedies.

Greenaway: "Virgil, way back, 100AD said 'an artwork has got to be in equal parts instructive and entertaining.' This film is instructive on how we feel about death."

Setting the Scene

The film takes place in a recognizable but dramatized depiction of England. Dramatized in a way "a child might remember it or come across it in the illustrations of children's literature." It's also dramatized through the lens of medieval and renaissance masters, which Greenaway is famous for reproducing. Each frame is considered as a standalone piece, and the position of the film comes through in the visuals.

Greenaway: “We’re constantly reproducing, for those who are in the know, the compositions of a lot of very important painting.”

26 Ways to Light a Scene

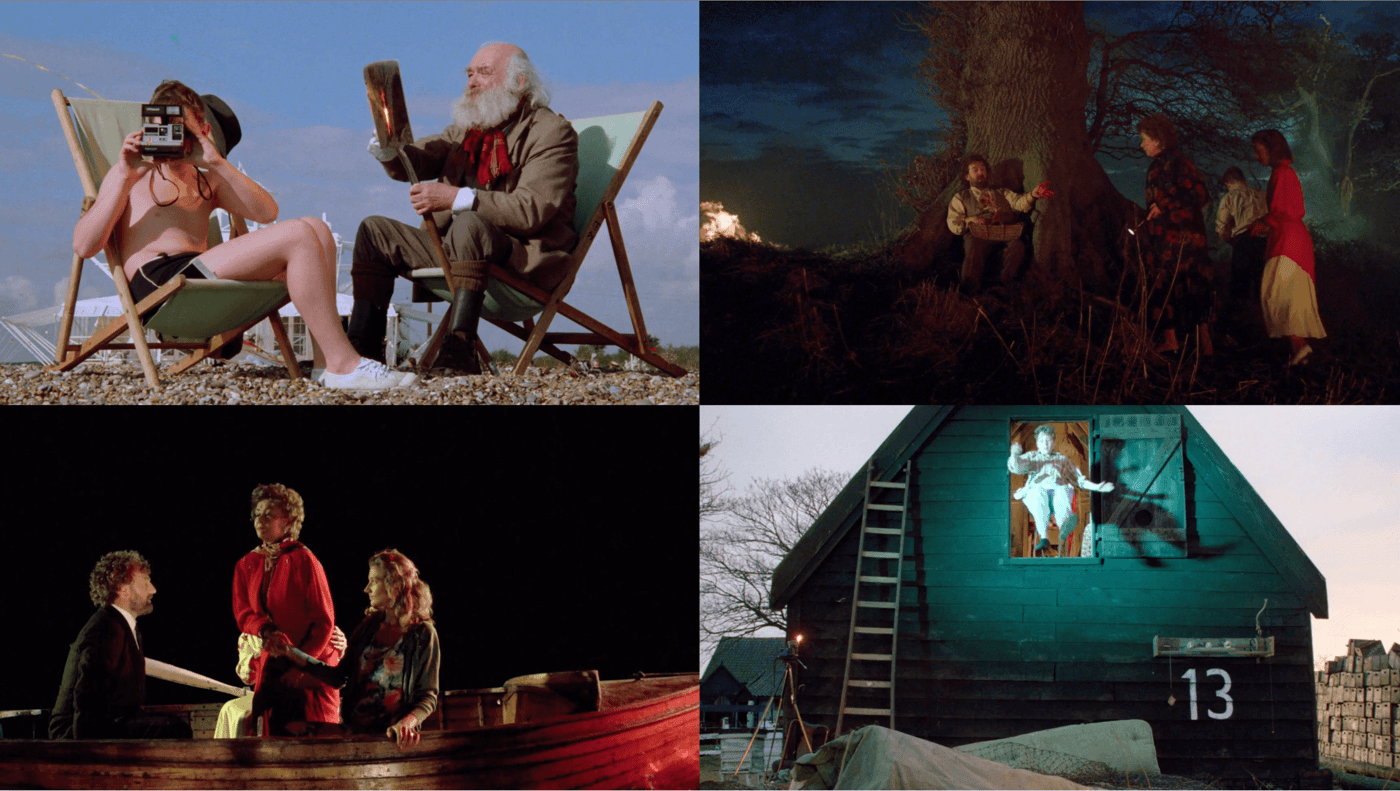

Before making the film, Greenaway wrote a list of 26 ways to light a scene, one for each letter of the alphabet. He spells out each way in this film: starlight candlelight, firelight, sunset, sunrise, lamplight, moonlight (good for the complexion) and so on. Here's four of our favourites:

1. Glinting off the back of a polished spade,

2. A bonfire illuminating a misty horizon,

3. Beams of a lighthouse oscillating and reflecting off rippling water 4. The flash of a self-timed camera.

Each form of lighting is active in the scene, a moving part of the images. This is the great advantage of cinema; the frames are very painterly, but they're also very dynamic. Scenes are often shot in the orange light of dawn or sunset, when both the sun and moon are in the sky. It's not just reproductions of artwork, but a way of extending the traditions of painting into the medium of cinema. Greenaway is making homages and making them new.

Greenaway: "Beyond painting, it's also looking at the 19th century novel, the 18th century symphony, things that took a long time to make and are extremely well-wrought."

Literary Influences: The English Novel

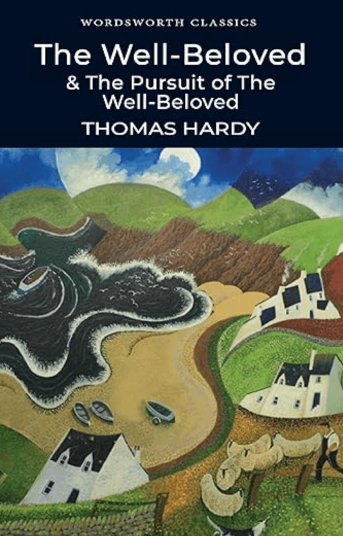

Though Greenaway avoids direct references, the parallels to Thomas Hardy’s The Well-Beloved are strong enough to be mentioned here. That novel, like this film, tracks the repetition of desire through three women with the same name. Like the trinity of Cissie Colpitts, Thomas Hardy's thrice-occuring Avice Caro feels like a single presence split into three generations, each drawing the male protagonist in only to leave him ungratified. Madgett, the coroner, suffers the same rejection: letting each woman get away with murder, and getting nothing in return. Incidentally, the writer character in the film (husband of Cissie 2) is also named Hardy.

Soundtrack: Michael Nyman and Mozart

As for the nods to the 18th century symphony, it comes through the soundtrack, which is all based on Mozart's Sinfonia Concertante, which both Greenaway and Nyman had been obsessed with for many years prior.

The piece first makes an appearance in Greenaway's earlier film The Fall, where Cissie Colpitts also makes her debut. Among the soundtrack titles, the most challenging composition is 'Trysting Fields' where Nyman says he "puts under a microscope Mozart's affective deployment of the accented appogiatura which partly accounts for the poignancy of the movement."

In this song, Nyman extracted every appogiatura from Mozart's piece, and make a song of his own with the details. It's complicated but playful; an appogiatura is a note which 'leans' on another one, deriving from Italian verb appoggiare, "to lean upon." On the sheet music, it looks as though one note is leaning on the other, pushing it down almost as if to drown it out. Below is an excerpt from Trysting Fields, where the appogiaturas, grouped in threes, almost re-enact the three women pushing their husbands beneath the surface.

Games

Throughout the film, Smut recites the rules of many games, some of which have been made up for the film.

The film is all about game-playing. And the big game Greenaway plays with us, the audience, is a number count: we start at one and finish at one hundred. The numbers appear in the frames like evidence numbers at a crime scene, or the patches of a paint-by-numbers grid, all propping up the layer of artifice between us and the story.

“It’s going to create a certain distancing effect, a sort of Brechtian alienation—I’m not here to give you escapist movies, I’m here to make a film. And I want to prove to you that the only thing you’re watching is a film. Just a film! It’s not a slice of life, not a window on the world, it’s a film. And films are deeply, deeply artificial, so I’m going to push hard on all that artificiality.”

Children's Games by Peter Breughel the Elder might be the most instructive work concerning Greenaway's approach to the film. Staged next to the bed in Madgett's house, the painting blurs the lines between childhood and adulthood by portraying children absorbed in games that mirror adult behaviour—competitive, imitative, and often absurd. In Breughel's image, distinctions between child’s play and adult life are superficial; both are governed by routines, social performance, and a kind of blind absorption in invented rules. Greenaway evokes Breughel in framing, colour palette, and staging, often reproducing scenes from the painting as tableaus in the film.

Greenaway: “That’s a sort of game-playing thing, but also a sort of heritage thing—there’s that very beautiful phrase by John Donne: “No man is an island” —no film is an island. Films are constantly, constantly, consciously or unconsciously quoting and repeating this huge heritage we’ve got, both in terms of literature and certainly in terms of painting. So let's do what we can to put as much information in on as many different levels to totally totally engage the audience. I would like to think I make well-wrought films that are capable of being continuously deciphered."

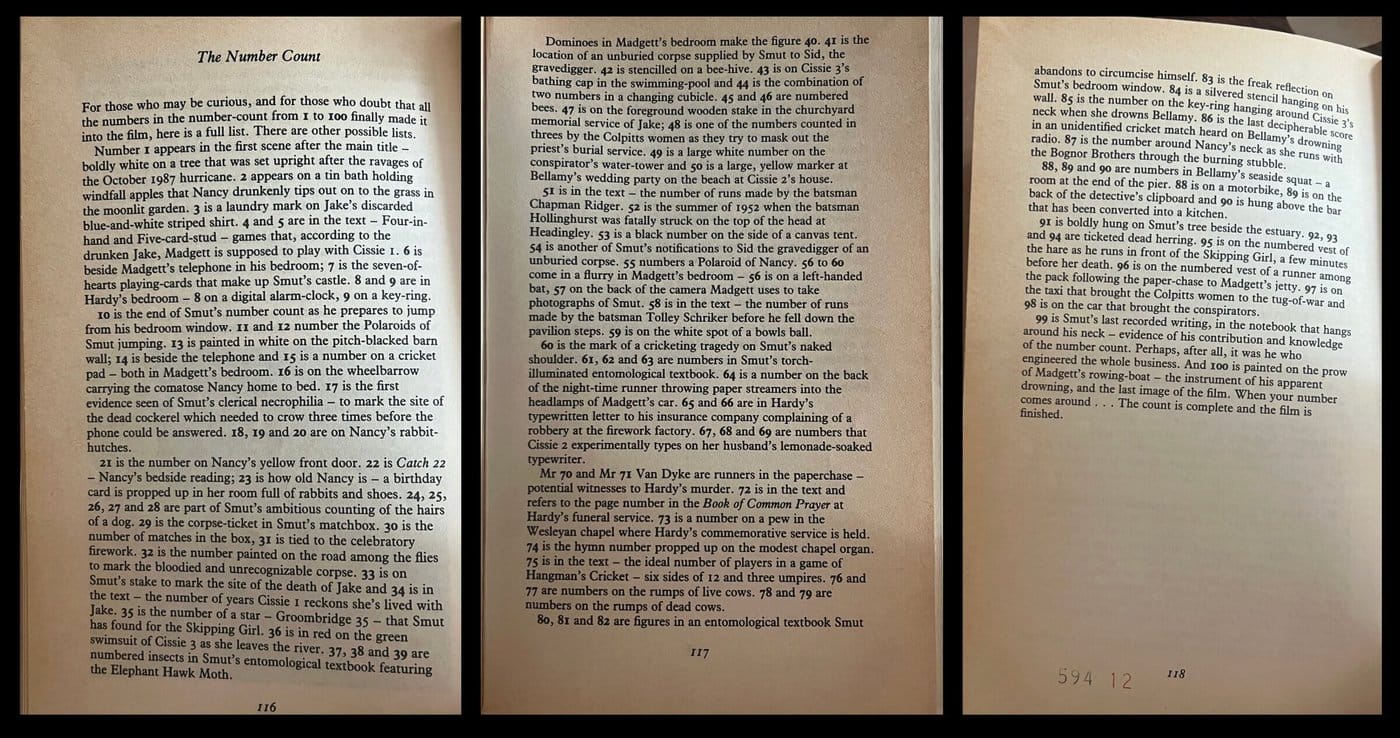

If you're watching this film and want to know where each number goes, the complete number count is listed in the back of the screenplay, which we've excerpted here. Below is the complete list Greenaway wrote out, but it's suggested there are other possible lists.

Drowning by Numbers is now available to watch on Eternal Family.

Written by Megan Switzer